Ukrainian photographer Stanislav Ostrous spoke with the masters and engineers of Kherson's boiler rooms, located in the most dangerous areas of the city. Despite flooding, shelling, and constant cold in the premises, these people continue to provide warmth to others.

The city of Kherson is located close to the front line, and some of its districts are under constant shelling. However, even there, people continue to live and work. Ukrainian photographer Stanislav Ostrous once again visited his hometown to record the stories of Kherson boiler room workers. “People are working to provide heat to a few residents who were unable or unwilling to leave their homes. I sincerely admire their work and dedication,” says the photographer.

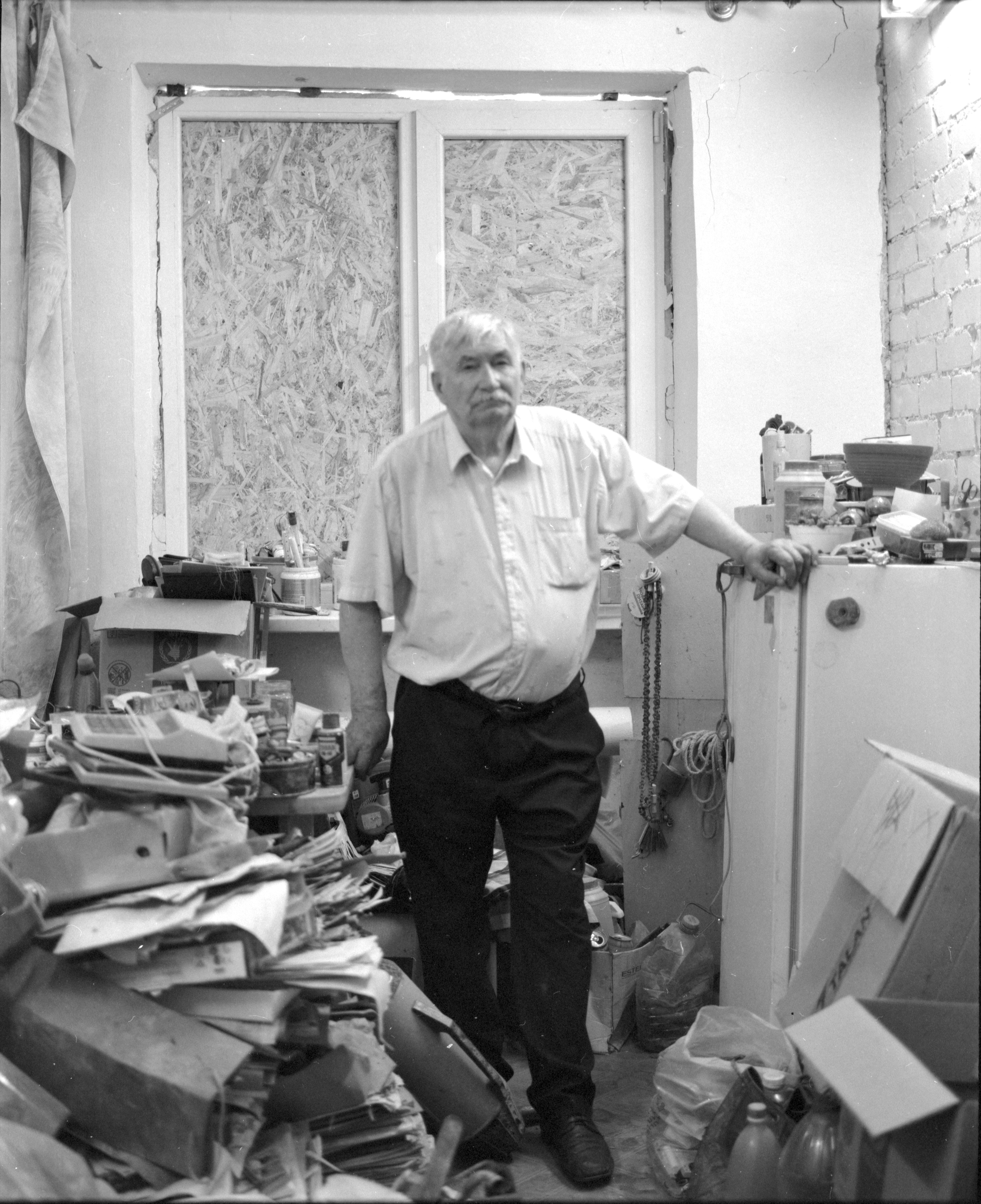

Stanislav Stanislavovich Kshanovsky

Currently, one of the boiler rooms, known as “Ostrovska,” is ceasing operations. Russian troops have damaged the bridge over the Koshova River, making it impossible to reach the boiler room, let alone operate it properly. An entire district of the city is at risk of isolation. Evacuation is currently underway, with the elderly, people with disabilities, and those with limited mobility being transported out first.

Stanislav Stanislavovich Kshanovsky, the master of the “Ostrovska” boiler room, has been servicing the boiler room since 2022. He came there immediately after the city was liberated from Russian occupation forces.

The island is one of the most dangerous areas of the city, as it is located near the line of contact that runs along the Dnieper River. In December 2022, the boiler room began supplying heat to the area again. People worked without days off for a month to prepare the boiler room for the heating season — they drilled a new well, started two boilers, one of which is operating at full capacity, and the other is an emergency boiler operating at 30 percent capacity. The boiler room foreman says that the main problem is a shortage of workers and power outages. “As soon as it ‘hits’ the brick factory, where we laid a new line, we are immediately left without power,” says Stanislav Stanislavovich. "We have to turn on the generator, which consumes 93 liters of diesel per hour. During the heating season, we burned almost 40 tons of diesel fuel. In January, we worked exclusively on the generator for 24 days." The boiler room operates under constant shelling, with numerous craters throughout the territory, broken pipes and ceilings in the small hall, crumbling slabs, and traces of hits in the direction of the boiler in the main hall. Fortunately, no one was injured.

Stanislav Kshanovsky lives in Kherson with his retired wife and son, who works as a doctor at a cancer center. Stanislav Stanislavovich left his home in Kindytsia, as the village is in the red zone and under constant shelling, and moved into his friends' apartment in the northern district of Kherson. Stanislav Stanislavovich is satisfied with the boiler room team. "I am very lucky that I don't have to supervise anyone.

Everyone knows their job and performs not only their duties but also other related tasks: they repair equipment and adjust machines,“ smiles the boiler room foreman. ”There are many needs, for example, we need insulation for pipes and lubricant, which cannot be delivered because the bridge is under constant shelling..." Today, the bridge is almost completely destroyed.

All the windows in the boiler room have been broken, but the workers managed to board up several windows with chipboard panels on their own. “Volunteers came and promised to help. However, they never returned,” says Stanislav Stanislavovich. "We need almost 1,500 square meters to cover all the windows. But the main thing for us is to protect the windows at least in the room where people are most often. Without windows, in winter it is as cold inside the boiler room as it is outside, with strong drafts, except that nothing drips from above."

During the flood caused by the dam burst at the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant, the Ostrovna boiler room was flooded up to the second floor. The foreman shows clear marks on the ceiling of the room where the water reached. All engines were restored, cleaned, disassembled, and dried, and the oil was changed. Every day, 20 electricians from all city boiler rooms worked on the site. The boilers were not badly damaged, only the screens were displaced by the impact. The next heating season is planned to be again with one boiler, without a backup, as there is no time for repairs before the start. “Given the announced evacuation of the residents of Ostrov, the relevance of the boiler room's work is highly questionable,” says Stanislav Ostrous.

Stanislav Kshanovsky shares his experience of living under constant shelling. He has learned to calculate when an enemy tank's ammunition will run out, to hide from drones, and simply to survive. “Recently, a drone with ammunition fell near the boiler room pipe, got caught in the branches, and couldn't take off. It was beeping and buzzing, and we waited four days for our sappers to arrive and take it away,” recalls the master.

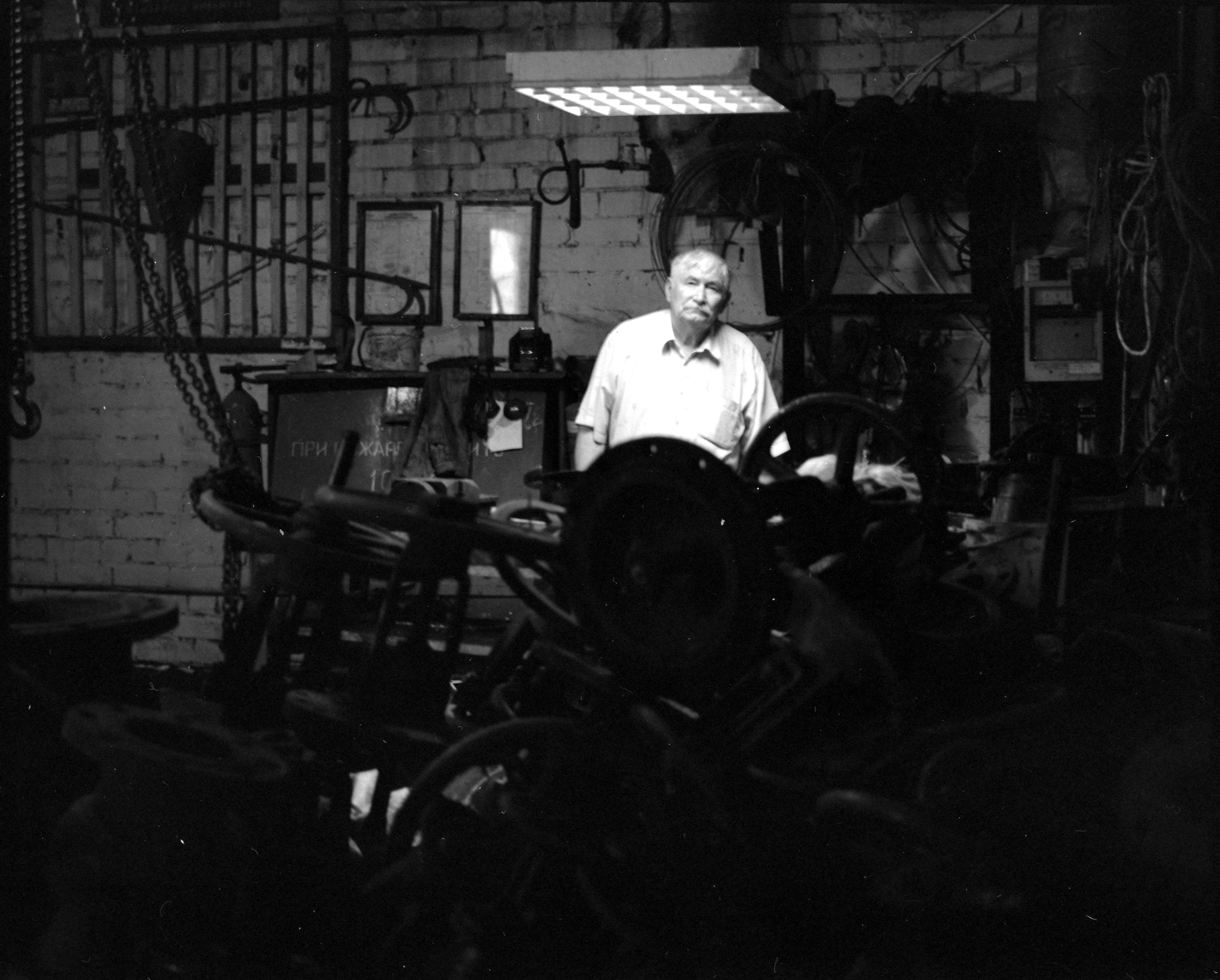

Igor Viktorovich Korzh

Igor Viktorovich Korzh works as a boiler room operator in Kherson at 115 Bogoroditska Street. He talks about the area that his boiler room heats. "Most people have left. There are still people living near the boiler room, but further on towards the port, there is no one left,“ says Igor Viktorovich. ”Yesterday, on Lisna Street, I saw a young woman who lives alone in a five-story building. There is no electricity, no heating, no water, no gas, but she lives there." Igor Korzh is an energy engineer by training. In 1979, he built the boiler room and had no idea that he would ever return there. “There is a war, and there are no jobs. I'm not interested in working as a security guard, so I agreed to work as a boiler room technician,” says Igor Viktorovich. "Now they are installing new equipment in the boiler room, a lot of new electronics. My staff consists mainly of women over sixty, and they don't really understand all this. With the old equipment, everything was intuitive — you lit the torch, put it in the furnace, and the heat was on!" The boiler room is now staffed mainly by people of retirement age. Many young people have either left or joined the army.

On January 26, 2023, a Grad rocket hit the boiler room, just as Igor Viktorovich was on duty. "The whole city rushed to the boiler room — the police and the management. All the windows were blown out, so they were boarded up with plywood. Now they have installed carbonate, as it absorbs shock waves, but it has been punctured in places by debris, because something is constantly flying around. Drones are flying all the time,“ says the boiler room foreman. ”Fortunately, there have been no casualties so far. One employee was hit in the back by debris, but it was just a bruise."

The vast majority of pipelines are located outside, so any damage can cause a lot of trouble. Even a small drone can rupture pipes. "Shelling, flying objects, and people go to work and work conscientiously. There is no other way. The whole of Kherson depends on these people. We will continue to work and start up the boiler room," says Igor Korzh.

Serhiy Petrovych Kozinsky

Serhiy Petrovych Kozinsky has been working as a boiler room technician in Kherson at 22 Gimnazichna Street since 2003. He recalls the difficult times during the occupation of the city, when there was no electricity or water supply. With the arrival of the Ukrainian authorities, things more or less returned to normal. “Last year, the boiler room heated 14 buildings, but it is designed for 48. The buildings around it are destroyed, and it is unclear what will happen this heating season,” says the master. “Many buildings have burned down, roofs have been damaged, internal pipelines have been damaged, and there are no residents.”

On May 12, 2025, a mine hit the boiler room and pierced the roof directly above the master's office. There were several hits in total, resulting in a crater in front of the boiler room, a damaged telephone cable, and a breach in the heating main. Everything around the boiler room was destroyed, and almost no residents remained in the area. “The most difficult part of our work is shelling, KABs, and rockets. If the boiler room is hit, no one will survive,” concludes Serhiy Petrovych. “There is nowhere to hide, and temporary shelters only protect against debris.”

Stanislav Ostrous was born in 1972 in Zhmerynka, Ukraine. He began taking photographs in 2012. He is a member of UPHA (Ukrainian Photographic Alternative) and MYPH. He was a finalist for the Leica Oskar Barnack Award 2025. Participant in the main exhibition of the Batumi Photodays festival (2016–2019). Shortlisted for PhotoCULT 2019. Currently lives and works in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

Photographer's social media: Instagram and Facebook

Contributors:

Researcher, author: Katya Moskalyuk

Image editor: Olga Kovaleva

Literary editor: Yulia Futey

Website manager: Vladislav Kukhar