On Photography Day, we focus on those who have only recently begun their careers. A new generation of photographers has emerged in Ukraine, whose names are not heard in gallery halls, but among the ruined streets of Bucha, Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Kherson regions — places where war became their first professional experience.

Many of them did not plan to become war correspondents: in peacetime, they studied, filmed local stories, or worked on art projects. But with the start of the full-scale invasion, the camera became a way for them to tell the world what was happening in the country.

Their photos are a new Ukrainian visual history: not only destruction, but also portraits of people who are holding on despite everything. The photos of these young documentary photographers have already appeared in international media, exhibitions, and competitions, becoming evidence of war crimes and the voice of Ukraine in the world.

Today, the Ukrainian Association of Professional Photographers is publishing a selection of their works and reflections on war and photography.

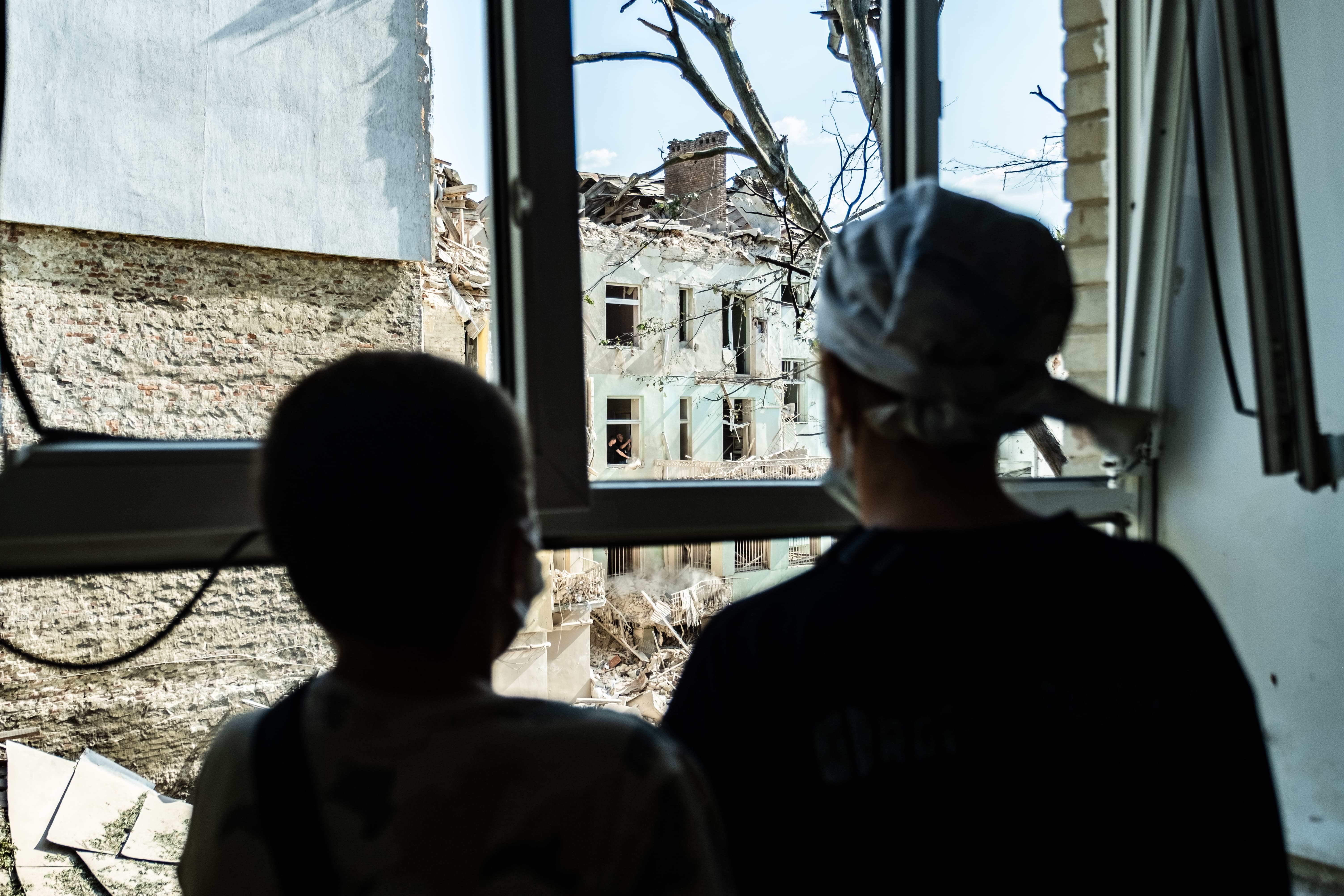

Iva Sidash captures the war from within, letting the experiences of those around her flow through her. For her, photography is not just a record of events, but a shared experience in which the boundary between the author and the subjects of the photographs disappears. She says: "Our war reality is fragile, painful, and damn unfair. The only thing I can do is capture it as I feel and see it. Almost all of my war photos are very personal because they are not just photos — they are people in their most difficult moments. I am there and become part of their experience — someone else's and at the same time very much mine, ours, shared."

Iva Sidash calls her photographs “very personal” because each one captures not only an event, but also a person in their most vulnerable moment. For her, war has not been a formative force, but rather a test: she does not allow evil to define her as a person or an author. Instead, closeness, care, and sincerity have become central to her—traits that resonate in both her words and her photographs. "War destroys. I won't say that it shaped me—I don't want to believe that evil has such power. Other things shape me: my choice to continue doing what I do, my responsibility to those around me, closeness, care, sincerity. War has only removed the unnecessary and set priorities. As a photographer, I have become slower: I listen more, put my camera down more often, feel the presence better. Sometimes it's difficult because, in addition to your own pain, you begin to carry the pain of others. As a person, I have become softer and tougher at the same time. I protect the values that I have cultivated in myself. I try to take care of myself and my loved ones in order to find the strength to continue living and loving," says Iva.

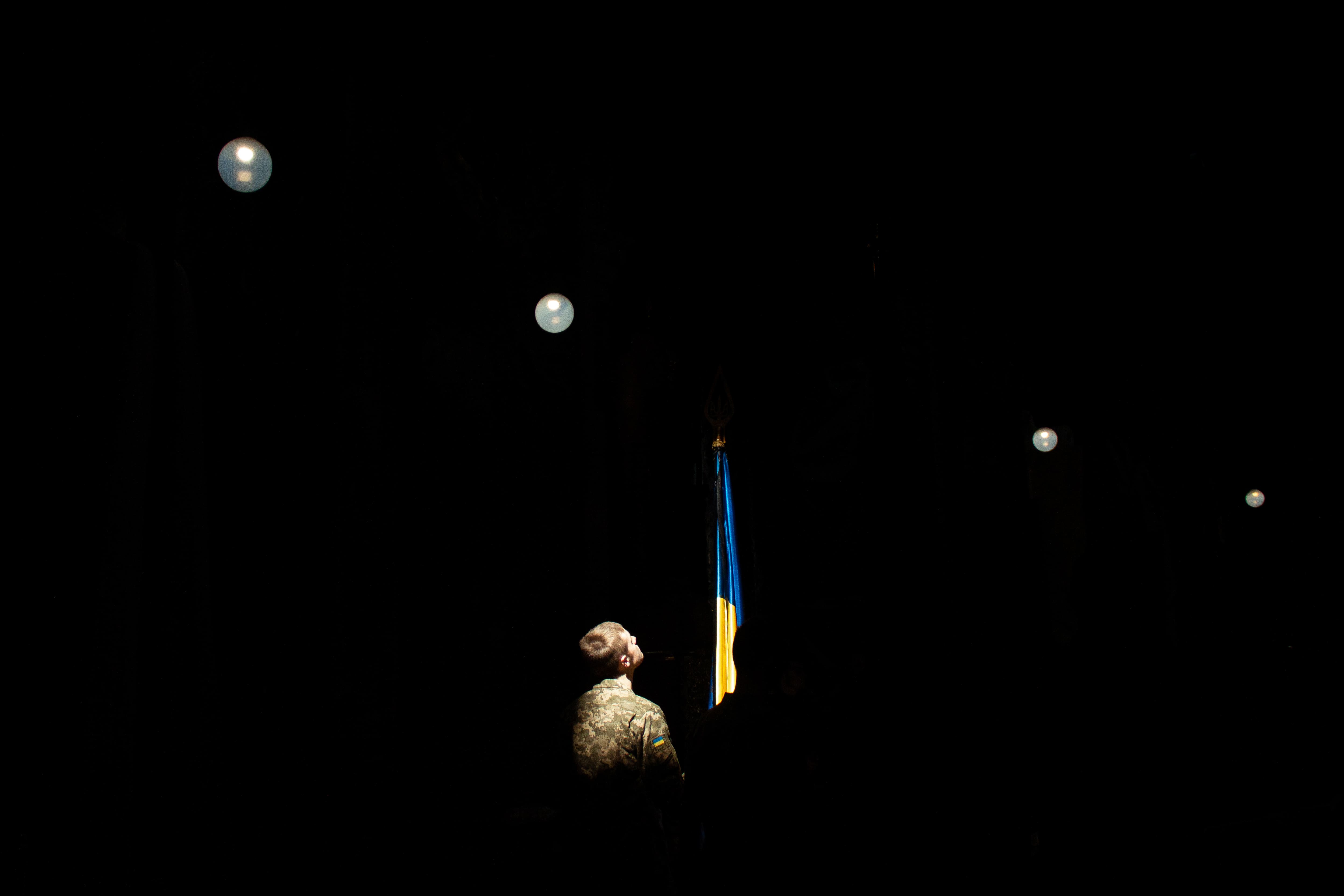

Photographer Petro Chekal talks about resilience not as a separate symbol or frame, but as the very ability of photography to exist and not disappear. His reflections are about the weight of the image, the limits of what is possible, and how war has exacerbated the eternal questions of photography itself:

"When it comes to Ukrainian photography in general, for me there is no one specific frame that symbolizes resilience. What is more important is that photography exists, that it is not silenced or erased, because there is an acute need to do it. It is because of this need that this war has become one of the most documented in history. And not only because of the need, but also because of the opportunity to take pictures: from frames showing the war according to the principle of “a good photograph is one that is taken close enough,” as in the works of the Liberovs or Maloletka, to Alexander Chekmionov's portraits of people in the rear or Taras Bychko's Polaroid portraits of artists. The very act of photographing and the relentless search for what and how to shoot is more important to me than any one specific frame. Of course, one could name dozens or hundreds of photographs that symbolize resilience, but it is more important to look at the bigger picture — at Ukrainian photography as a whole, because that is where true resilience lies."

He speaks about his own photographs without pretension: “As for me, I don’t feel that my photographs can be called a symbol of resilience. For the past few years, I have hardly taken any photographs on or near the front line. And I miss that, understanding its importance both for me and for Ukrainian photography as a whole. What I am doing now is related to a different level of photography — the one I want to transform. I would like to use the skills I have acquired outside the war zone for visual reflection and interpretation of what is happening and all the challenges we face."

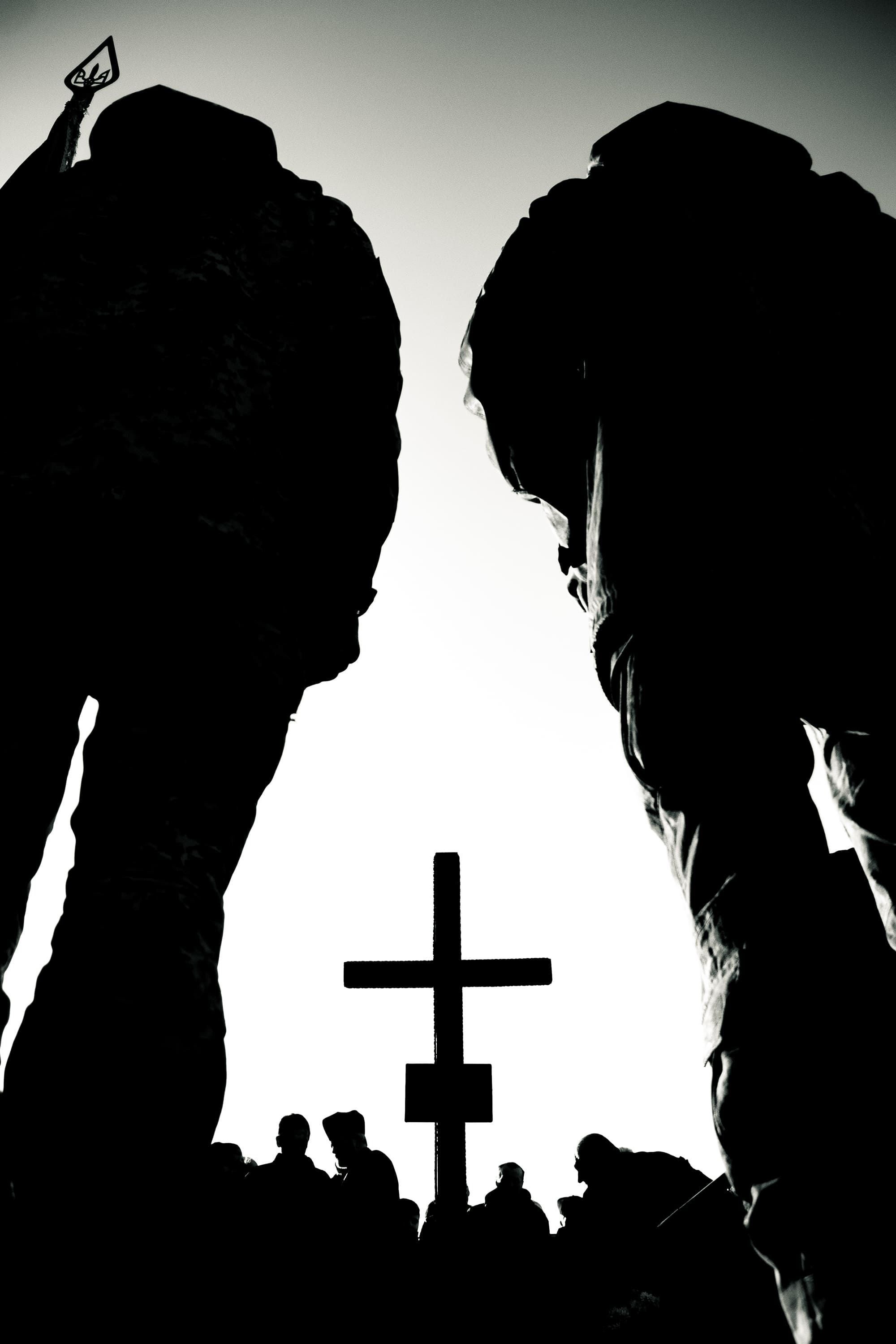

Photographer Oleksii Chystotin remained loyal to film even when digital technology seemed to be the only option. For him, analog photography is a way to slow down and look more closely at the events unfolding around him: "I usually work with analog photographic processes. I am attracted by the intuitive clarity of the technology, the ability to control the process at all stages of work: from shooting to printing and editing photos. Black-and-white film filters out unnecessary details and encourages you to work with generalized images rather than specific facts. At the beginning of the war, I tried my hand at digital photography, but quickly returned to analog. Although film is significantly inferior to digital technology in terms of speed, this is not a problem for me. I don't rush to publish material; I wait for time to set priorities: which photos are really important and which have quickly lost their relevance. I prefer long-term projects where it is possible to observe the development of events for years, analyze them, and not make quick conclusions."

Speaking about the future, Chistotin admits that he is not sure whether he will have a chance to take his main shot — documenting the liberation of Ukrainian territories. He sees this as a complex process in which photography is capable of capturing not the triumph, but the complexity and ambiguity of the moment. “Unfortunately, I am not sure that such an opportunity will arise, but I would like to photograph the liberation of the currently occupied territories. De-occupation is a complex process, where hope turns into anxiety about the future, and joy borders on grief for those who did not live to see this moment. In 2022, while photographing the liberated territories of Donetsk and Kharkiv regions, I was very surprised by the persistence of the local residents who had survived the occupation and were ready to start their lives anew and rebuild their region. Now these lands are again under threat of occupation, and some have already been captured by the enemy. Photography will not bring back the dead, and it is unlikely to help the living, but it can preserve the memory of this war, of the land and its people, their suffering and their struggle.“

Photographer Ivan Samoilov says that his return to Kharkiv at the end of summer 2022 was the moment when he first picked up a camera in a war zone. He recalls: “That was when I first visited Pivnichna Saltivka, which was about ten kilometers from the front line, and saw with my own eyes the scale of destruction that Russia had brought to my city. That day, I began documenting this war.”

Speaking about his own method, the photographer emphasizes that he tries to build his shots around the main idea of the story. He says: “It is important for me that the shot is emotionally and contextually strong, so I reject weak or random compositions. I only keep what helps to build a coherent narrative and emphasizes the key message of the event.”

Ivan is convinced that he will remain in the profession in the post-war period. He explains: "I was involved in photography even before the full-scale invasion began, at least I was taking my first steps. Now that I have gained some experience, I am unlikely to leave this field. In a country that has gone through such a long journey of change and difficult times of war, there will certainly be many socially important topics that are worth discussing through documentary photography."

Photographer Oleksandr Magula recalls his first trip to the front line after the invasion began: “It was in Cherkasy Lozova in early April 2022. Soldiers from the Kharkiv Territorial Defense Forces were stationed there, a rotation was taking place, and I came to report on it. That was the first time I photographed in a combat zone.”

Reflecting on the role of photography during wartime, Magula calls it paradoxical — both influential and limited:

“I understood how journalism works, and photography in particular. There is a certain chain: something happens, journalists record it, the photos appear in the media — and an impact occurs, sometimes even noticeable at the societal level. For example, when Ukraine needed artillery ammunition, photojournalists took pictures of our guns en masse. And these images became an argument in communication with partners — thanks in part to press services that understood this. But at the same time, I realized a paradox: photography can have an impact, but it cannot globally change the course of the war. It will not stop the fighting on its own. It is more like a pebble in a large wall of information resistance: it can be decisive at a specific moment, but it cannot turn the situation around on its own. This is probably the main lesson for me.”

The photographer adds that he wants to remain in the profession even after the war ends:

“I have a dream — to photograph car races, especially Formula 1. I hope the day will come when I can make it happen. But the experience of war photography will stay with me forever.”

For Georgy Ivanchenko, the war was not only a challenge, but also an impetus to choose a career path. He recalls his beginnings in documentary photography: "I studied journalism in Lviv for six months — precisely to learn how to photograph something socially significant, to work in a war zone. But the full-scale invasion significantly accelerated this process. I gave the keys to my apartment to the owner, scraped together two thousand hryvnia, got on a train, and left. And that's how I spent the next two years — constantly on the move, with my home in my backpack, a camera around my neck, and a complete lack of understanding of how everything works. When life puts you in a dead end, you flip a coin, and it chooses the vector of your next step. That's how I got into war photography. And it was a wonderful practical experience."

At some point, the ease and excitement of photography disappear. They are replaced by images that remain etched in your memory for a long time. For Ivanchenko, this turning point came during the morning shelling of Mykolaiv: “Photography is a very interesting thing. You need to be focused, quick-witted, assess the situation, and make the right moves at the right moment. It puts you in a state of flow that is incredibly exciting and gives you a feeling of happiness. But there are moments when you feel as if you are being hit with something heavy in the chest, head, and legs, when you lose your bearings, your breathing rhythm, and your inner focus. Mykolaiv, June 2022, 5 a.m.: An Iskander missile hits a five-story building. Many dead bodies. A man in a shirt, crying, collects film photographs around the house — his loved ones were inside, the rescue operation continues. Bodies crushed by concrete lie in the yard, and he looks and cannot understand: is it his mother-in-law or his neighbor? For me, it was my first encounter with something like this, and that morning is firmly stuck in my mind.”

On behalf of the UAPP, we sincerely congratulate all photographers on Photography Day. Dear colleagues, do not lose your inspiration to see and preserve beauty even in the darkest times. We wish you the strength and courage to capture pain so that the world can see the truth, and at the same time find light and share it. May your camera always be your reliable tool, and may the light fall in such a way as to emphasize what is most important.

.jpg)