Volodymyr Petrov is a documentary photographer and photojournalist, one of the co-founders of the community “Ukrainian Documentary Photography”. Today, he serves as a senior communications officer in the 33rd Separate Mechanized Brigade. His photos are a deep immersion in the story of the hero and an attempt to understand himself, a sincere account of events and a search for the truth.

— Tell me, please, when did the photo appear in your life? Who inspired you to shoot at that time?

— Everything is quite banal. The family was engaged in photography — there was a Zenit camera, and I was interested in film, technology. He started taking pictures — something worked, something didn't, and then he gave up. Invented this hobby at the beginning of the two thousand years. A friend of the family, photographer and photographer Igor Dedov, advised me a lot about shooting and supported me. I believe that I would hardly be engaged in photography without him, that photography would be in my life at all. Unfortunately, he is no longer with us.

We, together with Igor Dedov's family, went to Slovakia, in the conversation I mentioned a digital camera, and Igor replied that only film can give real quality. In addition, a film camera teaches you to think ahead and draw conclusions from successes and failures. I would advise taking pictures on film for those who are just starting to shoot. The process is longer, but in the future there will be more successful frames.

Now I have several digital cameras, but I mainly shoot on a Leica camera — because at work you need to take pictures quickly. On a film camera, I take pictures of important moments for me, which I want to save only for myself.

— What content do you put into the concept of documentary and street photography? How do you distinguish them for yourself?

“Most viewers of my pictures say it's street photography. I do not like this term, it is too narrow and does not convey all the meanings that I put in the photo.

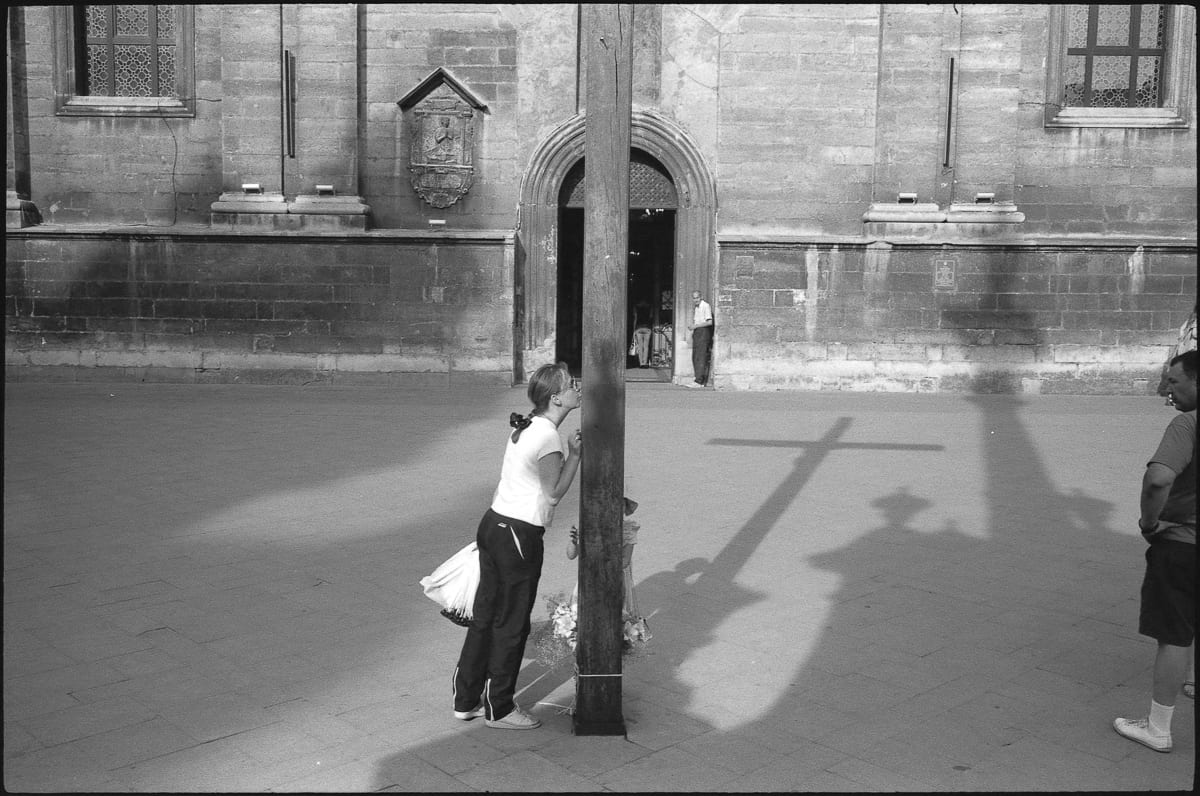

Street photography as a term appeared relatively recently, twenty years ago. He came with the popularization of photography on the street, when they shoot on a small camera and on the run, catch various unstaged scenes and charismatic types. Documentary photography looks deeper. When you shoot, you look at things differently and think differently. One of my friends, photographer Alexander Ranchukov said that documentary photography is a photograph of routine, routine.

Instead, street photography in a broad and popular sense now opposes the notion of routine. Modern street photographers are trying to find something unusual and non-standard, to catch curious situations. Photographers who worked fifty or a hundred years ago captured the mundane. They were not taking street or documentary photography, they were shooting what they were interested in. Classics of street photography, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eugène Atge, Brassay, filmed life around themselves. Eugène Atge photographed Paris before the reconstruction, and most of the buildings he photographed have disappeared. Paris has changed during the life of the photographer. Documentary photos may not be interesting to contemporaries, but they can be a discovery for future generations: how people dressed, what they did, what surrounded them.

Documentary photographers emphasize reality, but of course they cannot work, for example, like cameras in cars. Strong composition, light and curiosity about the world remain important. There is no need to look for something epochal or extraordinary, but, as Henri Cartier-Bresson said, you just have to always be prepared and then everything will work out by itself.

— What attracted you to photography when you started shooting?

— I was interested in showing the photos to Igor Dedov and my friends. The important thing was not even to take a picture, but to show it to someone. Photography was a meditative process for me, a way to immerse myself — I could walk 10-12 kilometers and not even get my camera out of my bag. I went to unfamiliar places, looked for interesting locations, sometimes there were interesting finds. There is such a saying that the legs work, and the head rests. Walking became a habit and became a kind of unloading from the routine.

When I found an interesting sketch, I was sure to take a picture. However, the process of finding a frame was also self-sufficient for me — this is its own philosophy. You listen to yourself and as if you learn to synchronize with the universe. Then you either resonate with him or you don't. If everything is the same, then the photos will be good.

— When did you feel that photography is a labor for you, not just a hobby?

— I was engaged in photography for about ten years, and then a post appeared on Facebook that President Yanukovych had not signed the Association Agreement with the European Union. People went to the Maidan and I also went there. I recalled there the emotions and moods I felt during the Orange Revolution when I was still a teenager. He came to the Maidan every day from its beginning to its completion. During the Revolution of Dignity, he made more than a hundred films. Realized that it was necessary to buy a digital camera because it had lost a lot of opportunities. I photographed no worse, but due to the specifics of my chosen media, it was necessary to spend time processing the photo. My friends and colleagues who worked with digital technology could get results here and now, as well as collaborate with top international media.

After Euromaidan, I had an ardent desire to take pictures, I realized the importance of the moment. I remember when we saw the “green men” on the TV screens, we understood that these were Russian military without identification signs. There was a military invasion of our country. I decided to buy a digital camera and go to Crimea to photograph the annexation. My parents did not share my initiative, but I could not have done otherwise. When I went to the store for a digital camera, I had one thought in my head — war, war, war. I walked through the barricades on the Maidan that had not yet been dismantled, looked at passers-by and wondered if they did not understand that we were attacked and the war was starting.

I was in Crimea for ten days and left before the so-called “referendum”. Without accreditation and with a Ukrainian passport, it became dangerous to be there. For several months I worked as a freelancer, offered photos to international agencies. In August 2014, I became a full-time journalist for the English-language Kyiv Post newspaper, where I worked for seven years. At the end of 2021, the media owner decided to fire the entire editorial team, which instead created The Kyiv Independent. For myself, he decided not to continue the path of photojournalist, because, working in the office, he reached the maximum. Nevertheless, he participated in the discussion of the name of the publication and insisted on the emphasis on independence. The media has been successful and I hope it will continue to be so.

— Please share, how was your first feeling and awareness of the war transformed after working in Crimea? What topics were you interested in when you worked at Kyiv Post newspaper?

— In the Kyiv Post newspaper, we had dozens of business trips to the ATO zone, followed by the PLO. I've been there dozens of times. I and my partner, journalist Ilya Ponomarenko, probably traveled around the entire Donetsk region.

The transformation of the gaze was too smooth to somehow signify or focus attention. After baggage trips to ATO, contrasts were felt. Today the situation is completely different, but at that time there was a significant imbalance between life in eastern Ukraine and, for example, in Kiev. There were civilians with their work, thoughts, current problems, etc., and in contrast to them, people immersed two hundred percent in the war. These opposites were transparent to each other, existed in parallel.

Today, when I put on the uniform, my perception of the people around me also changed, they began to be divided into civilian and military. When I came to the ATO zone, I asked myself every time, why should this guy sit in a trench, spend the night in a dugout, be deprived of the warmth of his family, etc., and not me. Why is he worse or better than me?

— You have been in the war since 2014, unlike many people for whom the war began in 2022. Tell us, please, about your feelings at the beginning of a full-scale Russian invasion?

— On February 24, 2022, I woke up at four in the morning from rocket explosions in Kyiv. Quickly grabbed the phone and ran into the bathroom, because there are no windows. I watched the news, corresponded with fellow journalists. Everyone who had been involved in the war before understood the real possibility of invasion. At this point, I have already completed dozens of home care trainings for journalists working in hot spots. Mentally and physically I was ready, I knew what to do and how. Of course, there was confusion, because no one realized the scale of what was happening, there was also fear, because people are afraid of what they do not understand.

In the first weeks of the full-scale war, I was at home in Kiev. We exchanged information with friends and colleagues, cooperated with several people on the car and went to work. There were many checkpoints in the city, blocked roads and bridges. Thanks to teamwork and a trusting atmosphere between colleagues, we filmed with a bang.

I soon began working as a fixer and producer for international media, including The Washington Post, because I quickly realized that as an independent photojournalist, I would not be able to compete with the top media on a decent level. I agreed that I would combine the work of a producer with photography - this is a non-standard scheme, but I managed to work with international journalists and take pictures for myself.

I gained important experience when I worked in the liberated Kiev region. At that time, the organization of the work of the media at the state level was only being developed, there was a lot of misinformation and rumors. However, there was also a critical need to document the consequences of the occupation, traces of the presence of Russian troops, where fighting, torture and bullying of Ukrainians took place, where bodies were shot with their hands tied behind their backs or the remains of several bodies burned. Everything was done critically quickly to show the world the consequences of the war.

— What struck you most in your memory from the filming of the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion?

— Everything. Photographers are people who capture a moment, capture a memory. Our memory works in a visual way. Everything we photographed becomes a memory that can be remembered in great detail, in small details. I remember the destroyed Irpin Bridge, through which local residents ran to evacuate, and how they were helped by territorial defense fighters. The soldier carries a machine gun, and his grandfather hangs around his neck, because he cannot move himself. A girl who had a small backpack and two cats. Baby carts left by their parents because it was impossible to cross to the other side of the river after them. I remember my grandmother, whom we helped to get to safety, and how she breathed hard and held my hand. I took a dozen good photos there, I remember every one of them because they are all special to me.

Older people recalled how their families fled the Germans during World War II. I went to the village of Demydov when a dam was blown there. A local SNS official said that his grandfather and grandmother, who also lived in the area, experienced the same situation “for the Germans” - then they also blew up the dam so that the tanks would not pass. It is very interesting when you look at such stories from the perspective of modern times. This, in particular, is documentary photography, when you look at things deeper, when you perceive everything in the distant perspective. When for you it is not just a grandmother or grandfather, but people with life experience and their own history. Photographs in this sense also need to be more profound — if you do not take into account the contexts, it is as if you are letting down the people who live the events.

— Tell us about your series of photos from the Revolution of Dignity. What pictures are most special to you?

— Very few photographers paid attention to the Maidan in a state of rest, usually photojournalists are interested in the action. For me, photos are special, when nothing happened, there was no resistance, no police attack or riot; when citizens waited, peacefully expressed disobedience, did not go home, but remained to live on Euromaidan; when even those people who were usually at home came and listened to the speeches of politicians and waited The reaction of the authorities. It was important for me to record the life of Euromaidan and show what happens when nothing happens. I shot a chapel, military tents painted by artists, construction helmets with Ukrainian ornaments and angels.

During the wait and after the first fighting, hundreds of self-defense forces began to form on Hrushevsky Street. Many believe that it was from them that the first volunteer battalions were formed. Gradually, Euromaidan was militarized, camouflage, metal Soviet helmets began to appear, and closer to February - armor vests. I was interested in seeing these changes. Euromaidan lasted almost three months, and the photos of most colleagues were taken in a few of the most active days.

It is difficult for me to single out one picture because many photos are important to me. However, there is a picture from 2014 that is very close and symbolic to me. On the Maidan, someone hung a boxing pear and pasted a portrait of Yanukovych on it. A person passed behind and asked someone for directions and the passerby pulled out his hand with an indicative gesture. I took a picture at that moment. I can't say that it turned out to be a super cool photo, but it was prophetic for me — a portrait of Yanukovych, distorted and wound to a pear with tape, and a hand that seemed to point him in the direction of escape.

I recall another moment from Euromaidan, when protesters at the entrance to the Dynamo stadium burned a fire in a barrel. If you turn the photo over, then the inscription “Crimea” is visible on the barrel. Maybe it doesn't matter to some, but I noticed this detail later and it made me wonder. It is interesting to rediscover such details and rethink the meaning of photography.

— When did the Ukrainian street photography community come into existence?

My colleagues and I talked a lot about photography and life in general. At some point, seven or eight years ago, Mikhail Palinchak had the idea to create a group on Facebook. We thought that we would distribute links to articles and lectures, talk about new photo books, post photos. Noticing that the group was rapidly gaining momentum, we decided to establish rules and selection so that the photos in the tape were of high quality.

Recently decided to rename the group to Ukrainian Documentary Photography. After all, all administrators of the group have been more attracted to documentary photography since its founding. We made a post explaining what is changing in Ukraine and photography is also becoming different. It is one thing to photograph the life of the streets in peaceful cities, another is the consequences of shelling, destruction, dead people and blood. These are also photographs taken on the street, but in a different context. There is actually no everyday life now, instead there is wartime life with the corresponding pictures that surround us. Even in relatively peaceful cities, the military in a coffee shop next to civilians will be perceived differently than in 2014.

When and how did you decide to join the army?

— The question of why others serve, and not me, I asked myself back in 2014. During Euromaidan at the extreme barricade on Hrushevsky Street, a young boy in balaclava and with a baseball bat asked why I was not standing next to him? This question caught me by surprise at the time and after a few seconds of reflection I said that I would do more with the camera than with the stick. At that moment I was convinced that it was. I am not an aggressive person. I had few conflicts in my life — I always tried to resolve them through communication.

It all started with the fact that my colleagues and I started discussing the new mobilization law. If I did not go to the troops from the first days of a full-scale invasion, then the sense of responsibility to those now serving prevailed. I decided that you should not expect anything and postpone the decision once again. There will never be a right moment because it is always scary to jump into the unknown, you just have to dare and take the first step. So I did, but with the difference that I asked friends and acquaintances beforehand, I was looking for a team and unit where I would need my skills and where I would be most effective. In the end, I was advised that there was a suitable position in the 33rd Mechanized Brigade. This is how my journey in the army began.

I invite all friends and acquaintances who know how to photograph, shoot videos or record interviews to the Armed Forces of Ukraine to communicate with military and civilians. The main thing is not to let the enemy divide us, as it was on the Maidan, because together we are a force, and one small person can influence global processes in society. I often mention the slogan of the Revolution of Dignity.

— Has your photo changed during your time in the Armed Forces of Ukraine? If it has changed, how?

— The news media needs to come, shoot a specific story, an episode from someone's life, make material, release it and move on. Documenters immerse themselves in the lives of their heroes, trying to look at these people in a longer time frame and explore their lives more deeply. When I took pictures in the ATO zone, I did not care, I was worried about the guys who lived in the trenches and dugouts. I didn't want anything bad to happen to them.

Documentary photography has the capacity for empathy, compassion for the person in front of the camera. It is important to penetrate deeper into the essence of things and the world of a person, to understand his life and to convey this in his photographs. For me, this principle remains unchanged, regardless of whether I am a military person or a civilian.

In your work, you see a lot of other people's pain. However, each person has a certain reserve of psychological resilience and empathy. How to convey someone else's pain in photos and not destroy yourself?

— The camera to a certain extent abstracts reality and helps to experience what is seen. The photographer partially hides behind the camera — both physically and morally, because he works on building a composition, searching for light and emotions. The brain focuses on other things, not on the human story and not on the events around. At the time of shooting, you may not realize the magnitude of the tragedy, and while viewing photos, emotions are simply knocked off your feet. However, it happens that during the shooting tears flow from the eyes or you want to laugh uncontrollably. As a child, my mother always told me that showing your emotions — laughing or crying, is normal and there is no need to be ashamed.

Every photographer has limits when it is worth stopping shooting. Someone is overwhelmed by what they see and cannot shoot further, and someone overpowers themselves and takes pictures further. Then he looks at the picture and realizes that it must have been worth stopping. This is the eternal dilemma of photographers — what should be taken and whether it should be published later. If a frame is not made, then it will forever remain in memory. Every photographer carries with him moments that he did not capture.

— Tell me, please, do you have any footage that you could not shoot and do you regret it?

— I have my list of unrecorded moments. On February 18, 2014, after the events at the intersection of Shovkovichna and Instytutska streets, protesters were pushed back to Maidan. When the “golden eagles” caught up with them, they were beaten by various means. My colleagues and I slowly descended and walked towards the Maidan. At some point, they saw several speeders near which there were a dozen people. Someone already had a bandaged head, someone was just beginning to bandage and apply bandages. People's faces were covered in blood. I took a few shots and moved on. Already closer to the Maidan, I realized that he was photographing on a camera without film. I had two cameras, and one just ran out of film — I wound up the coil, pulled it out of the camera and didn't charge the other. I asked my colleague to come back, because it was dangerous to walk alone at that time, but there were no more people near the ambulances. This happens and this case was a good lesson for me.

— Today it is difficult to surprise with footage from the war. Many of them are repeated. For example, a Paladin shoots, a beautiful flash, soldiers cover their ears, a shot occurs. Do you have a feeling that Ukrainian documentary photography lacks something today?

— The photographer is always missing something, the photographer is always short — there must be something that you did not take. Especially when events of such a scale as war take place. 95% of the photos of war events that we have now have were clichés since the time of ATO. I took all these pictures back then. Hundreds and thousands of photographers now come to the front to take similar shots. This is partly dictated by the conditions of war, there are many technical limitations and security reasons.

At the moment we are not fully aware of it, but the lion's share of the images of this war are taken on the phone and need to be shown. Most of my colleagues, documentary photographers and photojournalists, joined the army. If one of them takes a photo that is different from the frames of the previous ten years, then it is already a small victory. On the other hand, you can take a very good photo, but in one frame it is still impossible to convey such a comprehensive concept as war. Especially the big one that is happening now with us.

Russia's war against Ukraine is the largest in scale and resources since World War II. A colossal event, and it is a priori already the most documented war in human history. At the same time, we understand how little we show it and how many frames can be shown only after winning. However, we must always strive for more and better. Until this chapter of our life has ended and the next one has not begun, until then we must try to do your job, the one that you know best, and at the call of the heart.

In war, you can get somewhere and take an important photo. Not necessarily beautiful or unique, but important to the person depicted on it. This frame will be about this person in the here and now, because she is going through extraordinary events that have never happened before in her life. Maybe that person will not be there tomorrow. Therefore, each such frame is valuable.

Nevertheless, the photographer must take care of both his own safety and the safety of others. I try to discourage young people who do not have much experience so that they do not rush to go to war. I ask them not to put themselves and others in danger, not to create additional problems for the military who will have to take care of the wounded photographer. The decision to go to war must be conscious.

- What do you think is the role of documentary photography on the war and, in particular, on the war we are living in now? Is the image able to influence the perception of historical events in general?

- I have been in photography most of my life. I have been researching photography for almost twenty years and constantly increasing my experience and knowledge. It seems to me, even before the war, I got rid of the naivety that photography can make a difference, affect the world and decision-making. It is becoming obvious to more and more people that photographs are not to be trusted. At the same time, humanity has invented nothing as plausible as a photograph — the culmination of an extreme or routine event that conveys the essence of things.

Perhaps the Vietnamese or Korean wars were peak times for photographers' ability to influence the course of events. The conclusions were drawn by politicians, military and civilians. Photographers Chris Hondros and Tim Getherington died in Libya at the same time, and such events are influencing changes in war photography. Globally, we live in post-truth times and every day we can make sure that the world is not sustainable and its structure is not stable. Everything that we perceive as routine and stability can change very quickly and turn upside down.

Volodymyr Petrov (born 1988, Kyiv) — Ukrainian documentary photographer. He started photographing in 2004. From 2014 to 2021, he worked as a photojournalist in the Kyiv Post newspaper. Documenting Russia's war against Ukraine since 2014. One of the co-founders of the group “Ukrainian Street Photography” (currently “Ukrainian Documentary Photography” - ed.).

Photographer's social networks: Instagram, Facebook.

Contributors:

Researcher of the topic, author of the text: Katya Moskalyuk

Picture editor: Olga Kovalyova

Literary Editor: Julia Futei

Site Manager: Vladislav Kukhar