Roman Zakrevsky is a soldier of the press service of the 12th separate brigade of special purpose “Azov” NGU, a new member of the Ukrainian Association of Professional Photographers.

He started with his old father “Zenit” — he made stream photos, took portraits, worked in the media, dreamed of documentary and feature films. Today, he documents the war from the inside. We talked to Roman about how his photography has changed with the full-scale invasion, why film has become important again, and how he makes sense of his shots.

“Visual content constructor”

Roman, answering the question “Who are you now? Who do you define yourself by?”, he admits that even now it is difficult for him to give himself a single definition. But if I had to choose, the word “correspondent” seems to be the most accurate.

— It sounds a bit civil, but at the same time accurately conveys the essence of what I'm doing,— he says. — Although at the front I am mostly just called: “hey, photographer”. And that seems to be enough.

Before the war, Roman also did not want to call himself simply a “photographer”. It seemed too narrow. On Instagram, he signed himself as a “visual content designer”.

I've always wanted to do more than just shoot. I worked with different forms — I made sculptures, drew, collected objects in compositions. I am interested in combining what, at first glance, has nothing in common, but together creates harmony. This is my way of thinking — through the image, through the form.

Where we are

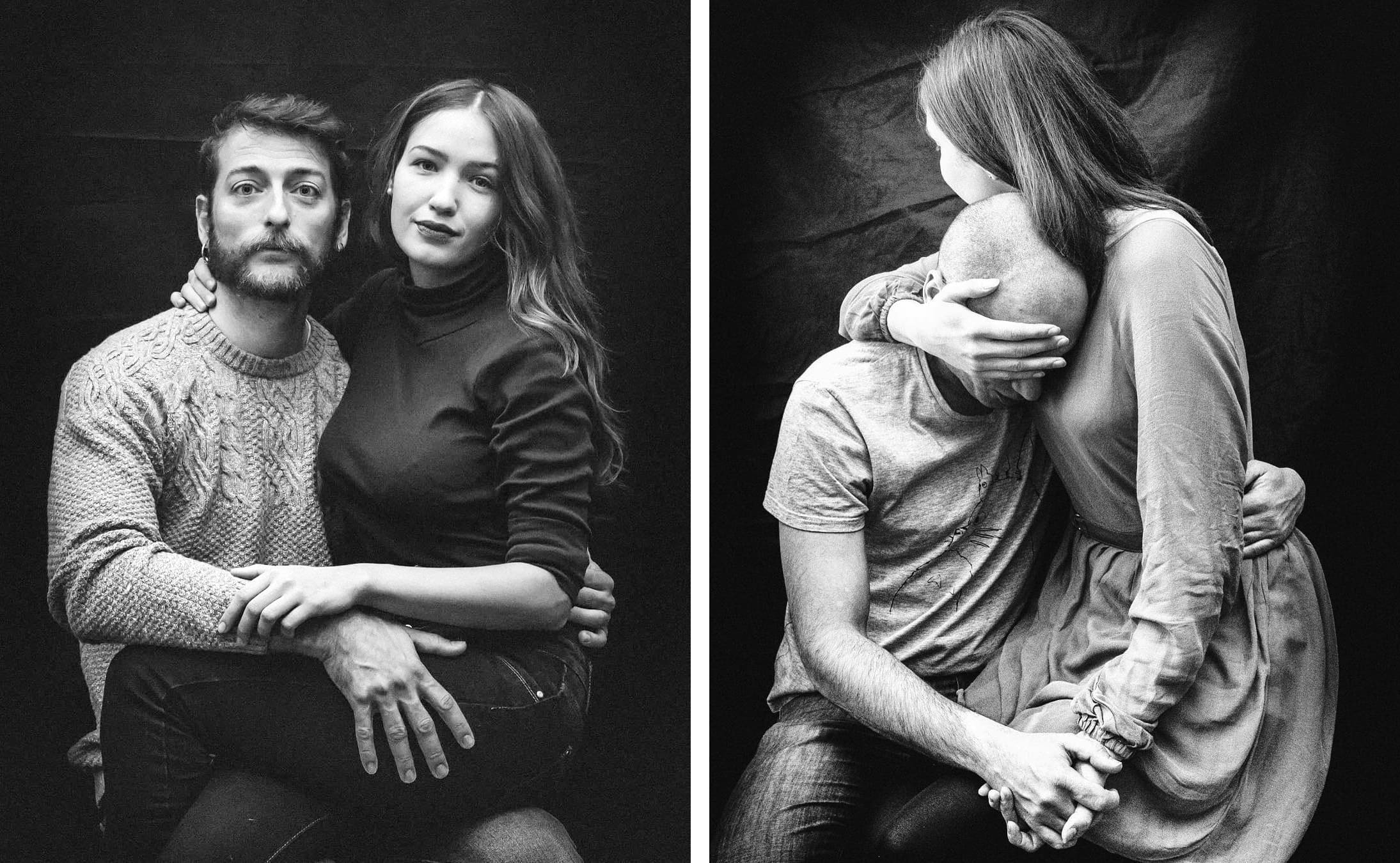

Before the full-scale Russian invasion, Roman most often took portraits. He says photography was often born out of conversation — from communication, which itself turned into an image.

— I talked a lot with people, and it was this communication that developed into photography— he says.

His biggest pre-war novel project was the series Where we are. He began filming her when he first moved to live separately from his parents. People came to Roman's house, sat across from him on a black cloth background — and he made a portrait.

It was a very busy time, 2016. Somewhere from February to June, new people came every day. At least two, there were five. Most of them I saw for the first time. I tried to show them that they were beautiful, that they were not “non-photogenic” as they thought of themselves.

The project spread through social networks — people saw successful portraits of friends, changed avatars, and asked themselves to be in front of the lens. After eight hundred people, Roman stopped counting.

It's still a bit scary to go back to that series. A very sensitive piece of my life is recorded there— says Roman Zakrevsky.

Portraits Series Where we areIt eventually grew into an exhibition. Together with the National Center of Folk Culture “Ivan Honchar Museum” Roman created the project “Identification.UA” — a combination of contemporary portraits of Ukrainians and archival pictures from the museum's collection.

— We combined my photos with those collected by the museum,” he says. And it turned out a kind of bridge between generations.

The exhibition was first presented in Kyiv, later she visited Chernihiv and the Ostroh Academy. After the exhibition, Roman simply gave away most of the portraits. And he himself continued to look for other forms of human inquiry, in particular through things — things.

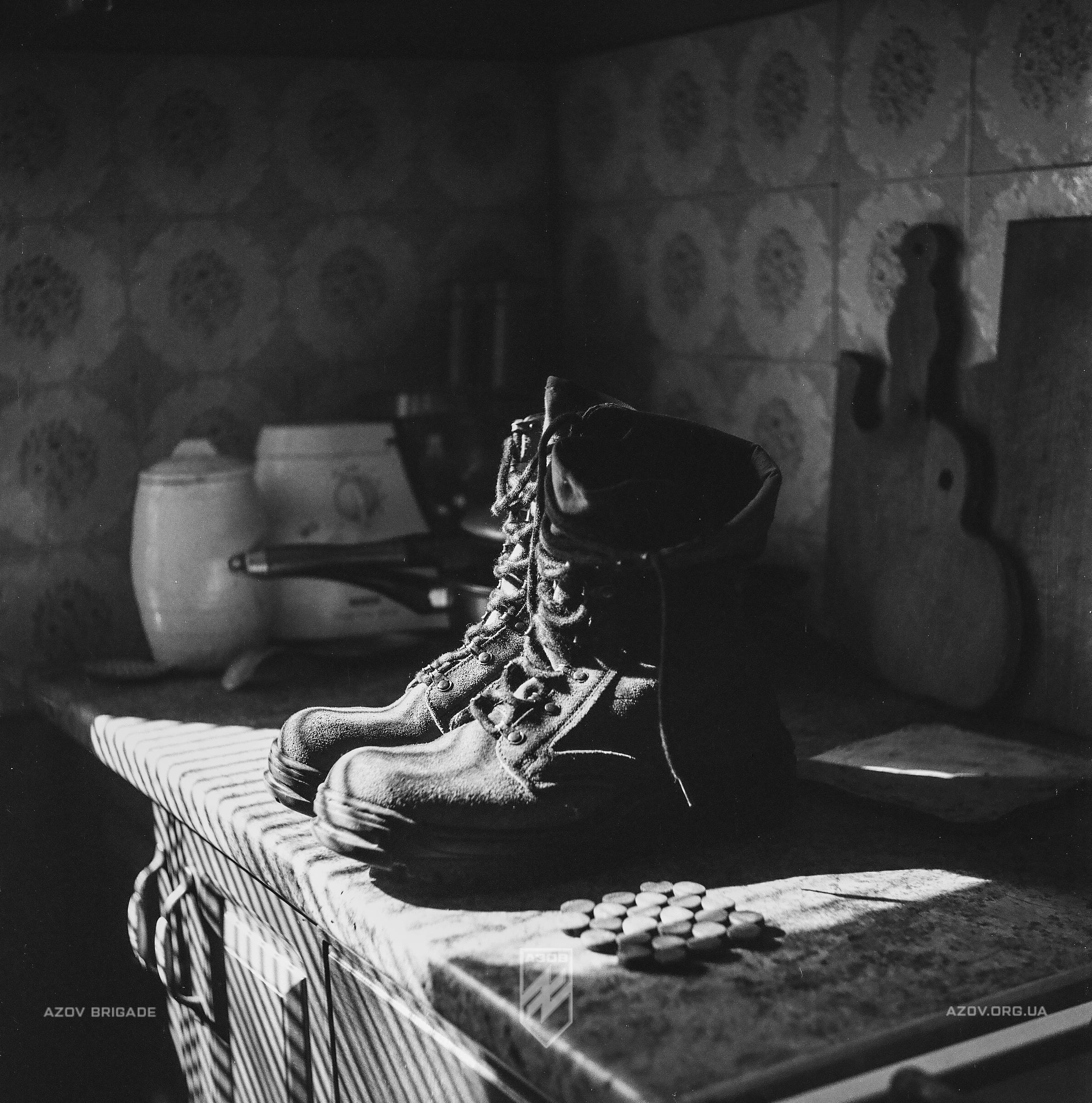

I call it things. This is when a person is not in the frame, but their presence is obvious— he explains.

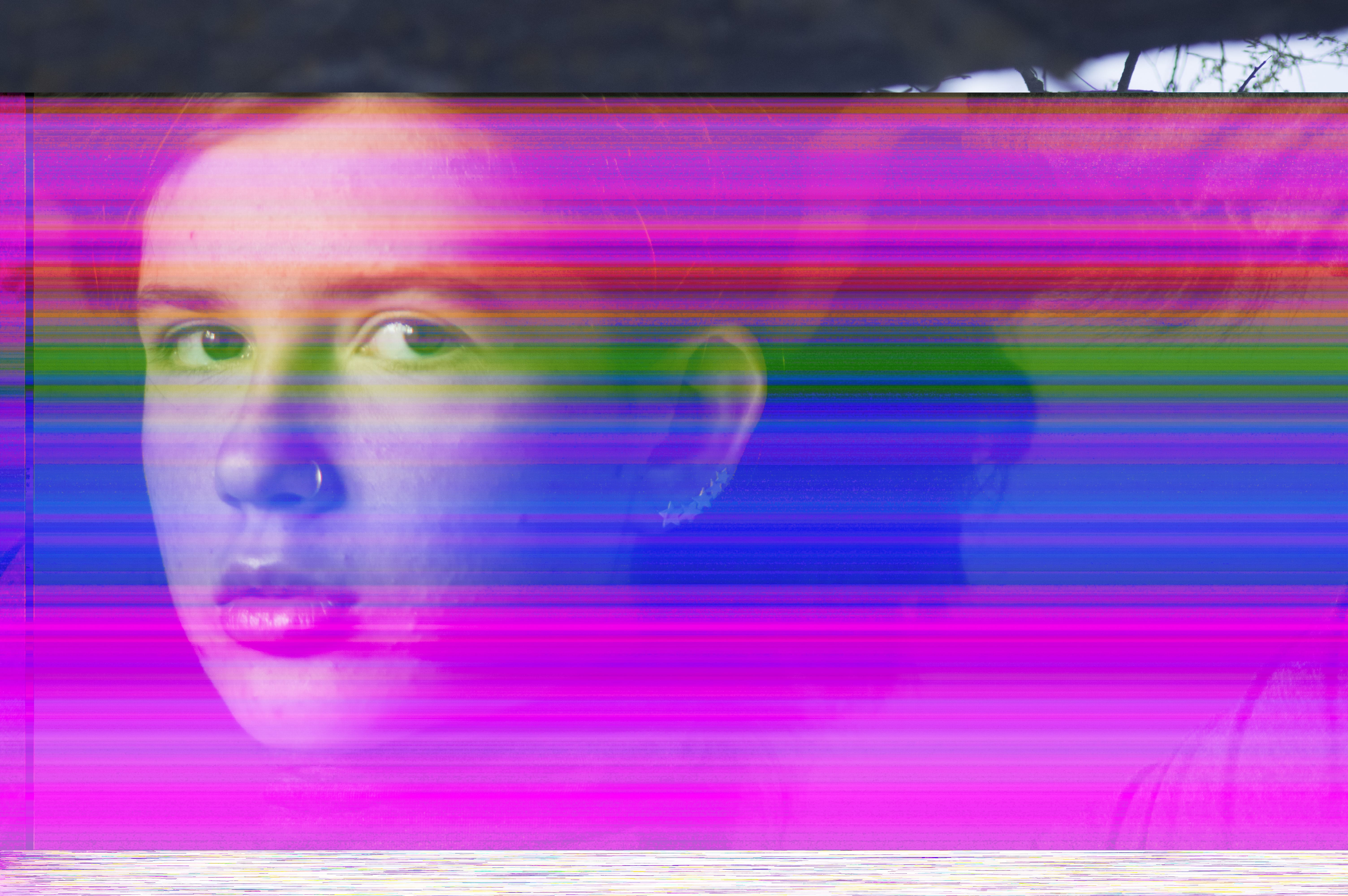

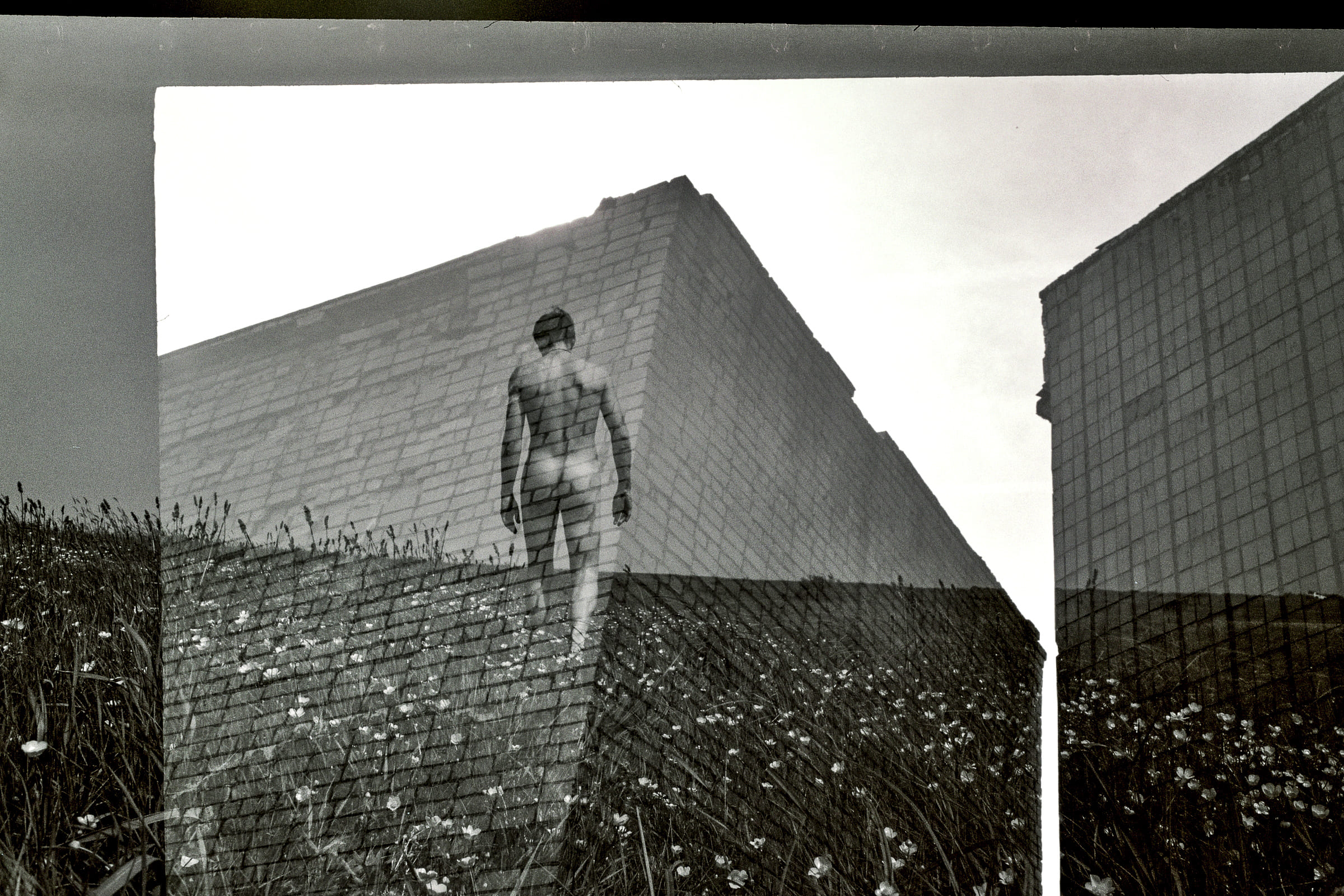

Sometimes it was a cup in a certain light. Sometimes things are left on the street. Such frames retain a sense of intimacy. Another direction of his search is the urban landscape, but not “postcard”, but random, urbanistic. He walked a lot in Chernihiv, caught simple but vivid moments. Roman also worked with film, especially fond of multi-exposition. One frame was layered on top of another — and something completely new came out.

— I didn't plan anything. I just took out the film, took it off and inserted it again. It's all about feelings,— says Roman. — I did not set limits on myself and did not hesitate to search. He broke off as much as he could.

Viewfinder

It all started with old dad “Zenita E”. Roman says he just picked him up — and couldn't put it off. He was captivated by the mechanism itself: the sound of the shutter, the tactile sensation of the metal, the sense of action.

— The camera was already charged with film. I started shooting just for fun— Roman recalls. - Then we bought another film with a friend - and carried away.

The real interest arose when he realized: the picture does not always correspond to what you see in the lens. It was this discrepancy that became the impetus to know this device more deeply.

— I was wondering: how do I make the photo match what I see in the viewfinder? It was a riddle that I wanted to solve, and I did it,says the photographer.

Roman told how one day he walked through the city with a tripod - snow fell, he froze, but he felt real happiness.

“I was catching shots, I was hustling and thinking, if someone had told me a few years ago that I was going to look for light and moment with my camera, I wouldn't have believed it. But I was unbelievably good— he recalls.

Then it seemed to him that the photo itself chose him, and not him her.

War as background, not center frame

Prior to mobilization, Roman Zakrevsky worked on television — at the Social Union in Chernihiv. He says that this work took almost all the time, but the camera was always nearby. He continued to shoot — preferably for himself, so as not to lose his visual form.

— It was not photojournalism in the classical sense, as Liberov or other colleagues who work with the world media,— he explains. — The only photograph of me that made it to the New York Times is rather a coincidence of terrible circumstances.

In the frame, Roman was not looking for drama, but for subtext — war as a backdrop. He was interested in the presence of war against the background of everyday life — not tears, but traces left behind. Children playing on a playground mounted in a crushed yard. Houses with gaps on the facades. Road with craters from mines.

— These are the kind of photos that don't scream, but they still say everything— he says.

After the siege of Chernihiv, Roman and his family were evacuated to Western Ukraine. In the Carpathians, he picked up the camera again — and then he had an idea, to which he plans to return.

— I want to combine photos from the siege of Chernihiv with photos of Carpathian nature. Two processes that occur in parallel: destruction and beauty, pain and restoration of life,— he shares.

New conditions — old optics

After February 24, Roman's photograph was no different — it remained the same in meaning, but the context changed. Now everything is shot in the “execution zone”. The same visual language, only with new circumstances.

— You can say that the values that I was guided by before the war only intensified here,— says Roman. — It turned out that this is really necessary. That I can be useful - both in the information struggle and in documenting reality. If you want, in propaganda. Because it's important too.

The only thing that has changed significantly is that he is again actively shooting on film, in particular medium format.

“I just get the order, and I take it.”

Roman Zakrevsky has been serving in the 12th special purpose brigade “Azov” for the second year. He says that the essence of his work has not changed - you need to take high-quality photos. But now it works in a war where there is no sustainable schedule or clear script.

— Here you can not predict exactly what you will shoot,” he says. — No one will say where the gun will stand, what microclimate there will be for shelling, how many times it will fire or who will be in the frame.

The task of the photographer is to obtain visual material to document the combat work, the destruction of the enemy or the daily life of the unit. These can be drones, artillery, trenches, evacuations, awards, portraits of soldiers.

— I just get an order — and I shoot, The photos you see on Azov social networks, in particular, are mine,says Roman.

He did not get into the unit by accident. Before the full-scale invasion, he worked with a friend, director Maxim Lukashov, on documentaries for Socialny — in particular about the consequences of the war in Chernihiv. When Max joined the press service of “Azov”, he mentioned Roman.

I think he was comfortable working with me. And when Azov was looking for a person who could make a documentary video, he offered me because I already had the relevant experience. We worked with him on three documentaries, where I was the cameraman, and he ---- director, including editing, — says Roman. — For the first time in my life, I made a normal resume — at 37. Passed an interview. And came to the performance area.

Photos waiting for their time

Roman admits: most of the pictures he took during the service are still not published. Some — due to military censorship or security requirements, some wait for their official publications. But there is another type of images — they are just waiting.

— For example, I have somewhere between 70-80 films shot. And of those, maybe 10 percent, a maximum of 20 is what I can show. There are things that I cannot lay out in my pages because, for example, they still have to appear on the pages of the brigade. And there are photos that simply can not be shown because of some details that can give the enemy unnecessary information. And there are still such photos... that are just waiting. I don't know what — time, context, or meaningthat will change over time — the photographer shares.

The novel recalls his early days in Azov: the camera in his hands was the only thing that kept him in good shape, when everything else was new and frightening.

“When I came here, all I could do was take pictures. Overcoming fears and tension, I just filmed. Most photos — digital — are still lying around waiting for their time. Because time makes a photograph, it gives it a meaning that is not always immediately visible and understandable. Yes, there are spectacular shots from the outings that have already been published somewhere - on the social networks of the brigade, in the calendar, but the bulk of the pictures are not about the wow effect. My approach is documentary. I do not invent anything, I do not interfere in the event. Sometimes a shot seems ordinary, and then, months or years later, you realize: it's important — because of the color, because of the person who was in the shot, because of the context that manifests itself over time. I do not see many contents yet, but I know that they will appear.

Three important frames

Among the thousands of photos taken over the years of filming, there are several that Roman remembers especially clearly. Not because of the perfect composition or exposition — but because of the experience behind them.

— A good shot is the one that got into the New York Times — he says. — It was a kind of career peak and at the same time a double event. On the one hand, it is very cool — I have been photographing all my life and often faced the misunderstanding: “Why are you doing this?”, “Find a normal job”, “Buy yourself a normal camera”... And on the other hand, this publication was made possible by a real, terrible event.

Roman made that shot a hundred meters from his own home. He says: In his youth, he dreamed of photographing the war — in Sierra Leone or somewhere in Africa. But the war came to his house.

You have to be careful with dreams.— concludes the photographer.

Roman calls the second photo a “personal song from the album” — not a hit and not a cover, but a deep track to which you return again.

— I have in my archive a vertical shot taken during my first outing in the infantry — in a trench. At first, I just liked the colors — the spots of light, the space. And then I saw in these spots the back of a fighter who went into the dungeon. And it was such a moment: as if something primitive, cavernous,— Roman recalls.

This photo conveys the psychological state of Roman in the first days of combat. It is hardly known to anyone, but it is important to him.

— In such cases, you realize that likes do not matter. This photo preserves my experience. And that's enough,— he adds.

The third series is the most painful. These are portraits of those who are no longer there. Roman photographed people and sent them pictures, and later saw them in the tape as dead fighters.

War is such that it takes lives. You photograph a person, you give them a portrait, and then you see them in a tape “with a shield and with a sword.” And you know — everything. I remember these photos very clearly. They stay with mesays Roman.

About game cinema and poppies

In the creative work of Roman there is also experience of working on feature films. Remembering the shooting of the feature film, he smiles - the tape has already been mounted, and he never had time to watch it. Life changed rapidly: the director had a child, a full-scale war began, and the viewing was constantly postponed.

The film seems to exist, but I still don't know when it will be shown.says Roman.— But there is a tick: I always wanted to make a movie. How to write a good poem, publish a book, play a movie and make a movie.

The shooting of the film took place back in 2017 or 2018. Its working name is “Gift”. This is a chamber story about two introverts trying to understand themselves and each other. Roman liked filming a feature film. He says it was a real thrill — the team, the support, the synergy. Compares with the feeling of the first parachute jump: excitement, joy, absolute novelty.

One of the scenes of the film was to be an episode in a field of poppies. And they really found such a field — in the village of Bilbasivka, which later ended up in the zone of hostilities in Donbas. Roman then plucked a small poppy flower and signed for himself in remembrance.

- Then, when I had already started serving, after another trip to the infantry, I came across a similar field with poppies near Kramatorsk.— he recalls. — It was very symbolic.

The film has not yet been released, but Roman hopes that his time will still come.

I think he will still have a chance. Maybe somewhere at the festival. His time is yet to come.

Presence, Change, and Invisible Limits

At the end of the conversation, we ask Roman one of the most banal but at the same time the most open questions: does he have an idea or a frame that he dreams of shooting? Or maybe something I'd like to repeat?

The novel tells about the idea of the exhibition in two halls: in the first one there are portraits of people who do not show any signs of disability. Just the face, the presence, the looks. In the second are the same people, but with physical features that previously remained hidden.

— A person walks in, sees photos, looks in the eyes. And then he goes to the second room and realizes: these are all the same people, just a context appeared, which was not there at first. And this context is also important. — explains Roman Zakrevsky.

He adds: this idea is still alive, it is changing. At the same time, he is interested not only in the subject of vulnerability, but also in the sense of change — in man, in time, in space. In this sense, the observation of one's own daughter acquires special importance.

— I have a daughter. She is growing. And I really want to capture this change — not literally, but figuratively. I am interested in how man changes in time, how he affects the space around him. It's not about a plot in the forehead, it's about a photo that first gives a feeling, works like an image, like something in the first three seconds. And only then you realize what you see,says the photographer.

The novel is not about the literal, but the tension, the silence, the touch. He is interested not in form, but in presence.

I want the photo to work as a presence. Like the silence that speaks.

Roman Zakrevskyi— Ukrainian photographer and videographer, known for his deeply sensitive approach to human image.

Born in Chernihiv, he has been engaged in photography since 2005. In his works, he combines reportorial accuracy with an author's vision, focused on emotions and the inner state.

Before the war, Roman worked mainly in color — this is how he saw and conveyed civilian life. The transition to black and white format was a natural change for him already during service at the front: only in the second year of his service in the army, he began to shoot on black and white film. The war in color, he says, is perceived unnaturally, causes dissonance - instead, the black and white image allows you to focus on the main thing.

He is convinced that the eyes are the strongest tool for transmitting feelings, and the authenticity of the frame begins where a person ceases to “play” in front of the camera.

The exhibition has been running since 2006. His works were exhibited in Ukraine (Kiev, Lviv, Chernihiv, Donetsk, Ostrog) and abroad, in particular in Austria. In recent years, he worked as a videographer at the TV channel Sociolne Chernihiv, and also made documentaries and feature films.

His photographs have been published in Ukrainian media (The Ukrainians, The Reporters, “Local Stories”) and international publications, including The New York Times and Wyborcza.pl. Zakrevsky continues to work at the intersection of art and journalism, capturing important moments from the life of the country and its people with maximum empathy and sincerity. Currently serving as part of the 12th special purpose brigade “Azov” of the National Guard of Ukraine.

Photographer's social networks: Facebook, Instagram

Contributors:

Researcher of the topic, author of the text: Vira Labych

Picture editor: Olga Kovalyova

Literary Editor: Julia Futei

Site Manager: Vladislav Kukhar