Sloviansk, Kramatorsk, Druzhkivka, and Kostyantynivka are cities that are part of the Kramatorsk-Kostyantynivka agglomeration. They are of strategic importance and form the basis of Ukraine's defense in Donetsk Oblast in the Russian-Ukrainian war. At the same time, the city of Kostiantynivka occupies one of the key positions in the Russian army's summer offensive. The Ukrainian Association of Professional Photographers analyzes the narratives and fakes spread by enemy propaganda in Kostiantynivka since the beginning of the war in 2014: from the “main base of pro-Russian militias” to the “gateway to the last agglomeration in Donbas not controlled by Russia.”

2014. “Base of pro-Russian militias in eastern Ukraine.”

In the spring of 2014, the Kremlin's special services launched an armed aggression against Ukraine. In April of that year, Russian hybrid formations entered cities in eastern Ukraine and proclaimed them the territory of the “DPR.”

On April 28, separatists seized the city council and police department in Kostiantynivka, two weeks after “little green men” (unknown armed men in camouflage — ed.) appeared in Sloviansk.

At that time, Russia refused to confirm its presence in the war. Instead, Russian propaganda painted a picture of a civil war that had begun in eastern Ukraine. “After the revolution in Kyiv, fueled by the situation in Crimea, Kyiv's aggressive rhetoric, and anti-Bandera propaganda, the residents of Donbas took up arms,” wrote the propaganda outlet Gazeta.ru.

The Slavyansk scenario was repeated in Kostiantynivka: at the end of April, a group of unknown armed individuals seized the police station and the city administration building in the city. Propaganda called them “militiamen,” “a community of people who are ready to sacrifice their own and others' lives for separation from Ukraine” (Gazeta.ru).

“Kostiantynivka, a city in the Donetsk region with a population of almost 80,000 people, located approximately halfway between Donetsk and Sloviansk, has become the main base for pro-Russian militias in southeastern Ukraine” (Gazeta.ru).

Russian so-called “war correspondents” confirmed that the ‘militia’ were serious: “armed to the teeth,” the buildings they seized were “solidly fortified with barbed wire, concrete blocks, sandbags, and ‘hedgehogs.’” The seizure of government buildings was explained as a “necessary measure before the referendum scheduled for May 11,” similar to the one that took place in Crimea (Gazeta.ru).

Russian media spread narratives that romanticized the events and created a pseudo-reality in eastern Ukraine for Russians and pro-Russian local residents.

Konstantinovka appeared in the Russian media as a place full of hope and desire for federalization. This was supposedly evident in the eyes of the city's residents and on the walls of buildings, where slogans such as “Stop NATO,” “Donbas, rise up,” and calls to “repeat the feat of our grandfathers” were written in chalk and spray paint. Historical parallels with the Bolsheviks and the “Great Patriotic War” were obviously intended to prepare the Russian population for the sacred war that awaited them. Gazeta.ru reported that “many militiamen sincerely compare themselves to the Red Guards in the war against the fascists: with a Berdan rifle on their shoulders, as he (the separatist — ed.) explains, to fight the fascists.”

Documentary photographer Anatoly Stepanov, who witnessed separatist demonstrations in Ukrainian cities in the east and south with his own eyes, said that the pro-Russian protests were more like riots. As the photographer put it, “all sorts of scum, outright drug addicts, took up automatic weapons, went to the checkpoints, and began to lay down their own rules.” However, Anatoly Stepanov noted that in addition to these people, there were also trained and well-organized strangers in camouflage — Russian special forces, whom the Russians passed off as local activists and volunteers.

On April 13, 2014, the Ukrainian authorities announced the start of a large-scale anti-terrorist operation (ATO) to liberate the Russian-occupied cities in Donetsk Oblast. However, the liberation did not happen quickly — the siege lasted two and a half months. Ukrainian defenders managed to gain a foothold on Mount Karachun, near Sloviansk — one of the four cities of the Kramatorsk-Kostiantynivka agglomeration.

The mountain was of strategic importance, as it allowed control over the city of Sloviansk itself and its logistical routes. There was also a television tower on Karachun, which was the site of bloody battles.

“Next to Kostiantynivka is Mount Karachun, where there is a television tower,” my interlocutor explains. Ilyich bequeathed to start with the telephone and telegraph, and here the revolutionaries are starting with it to broadcast Russian channels and block Ukrainian ones.

"On May 2-3, they launched a missile strike on the Ukrainian army, and they only had time to carry out the bodies. Well, today life in the city has not changed, most residents support the DPR, they are fed up with everything, and they do not recognize the authorities in Kyiv. The DPR is distributing weapons: come, show your documents, and after verification, take them" (Gazeta.ru).

One of the tragic episodes in the battle for Karachun was the shooting down of a helicopter and the death of Ukrainian soldiers.

On May 29, 2014, Russian troops shot down a Ukrainian Mi-8 helicopter. Around noon that day, a general delivered ammunition and supplies to a checkpoint in Karachun by helicopter and flew on. The aircraft, returning from a mission in the combat zone, was shot down by Russian militants using a portable anti-aircraft missile system. Eleven soldiers from the Interior Ministry's special forces and guards, as well as Major General Serhiy Kulchytskyi, were killed in the Mi-8 crash. He became the first general in the history of Ukraine's independence to die while performing his duties. A memorial was erected in honor of the crew near Mount Karachun on the highway between Kramatorsk and Sloviansk," recalls photojournalist Oleksandr Klymenko in an article by the Ukrainian Association of Professional Photographers. According to Oleksandr, he already understood then that “this was not an anti-terrorist operation, this was a real war, people were fighting and there was shelling, traces of mines and bullets.” The photojournalist flew three times on board the Mi-8 to deliver military aid, food, and water to the defenders of Karachun.

In May-June, the Ukrainian military liberated a number of settlements and destroyed the militants' fortified areas. On July 5, 2014, Ukrainian forces entered the captured cities, including Kostiantynivka, and the militants fled to Donetsk.

Having failed to achieve the desired effect, the propaganda began to stir up fear and intimidation: "After the retreat of Strelkov's troops (a Russian FSB agent and leader of the ‘DPR’ militants — ed.) from Sloviansk and Kramatorsk in early July, the cities returned to the control of the official Kyiv. Against this backdrop, it is increasingly difficult to imagine a peaceful future for the region" (Gazeta.ru).

2015–2022. “The most frightening symptom of Kostiantynivka”

In cities that remained under Ukrainian control until the full-scale invasion, the Russians tried to destabilize the situation and divide Ukrainians. To this end, they used shelling, local collaborators, and any events that could appeal to emotions.

In Kostiantynivka, in particular, separatists took advantage of a tragedy that occurred in the spring of 2015 involving Ukrainian military personnel. An 8-year-old girl was killed under the wheels of a military vehicle, and another child and a woman were hospitalized with injuries.

“The most important event in Ukraine in recent days was the tragedy in Kostiantynivka, where a drunk ‘ATO soldier’ ran over eight-year-old Polina with his MT-LB tank, simultaneously running over the remnants of Ukrainian statehood” (Ukraine.ru).

The General Staff acknowledged that the soldier was intoxicated. A criminal investigation was opened.

Pro-Russian forces stirred up discontent in the city, turning locals against Ukrainian soldiers. Russian media reported that an “assault on army barracks with bare hands and Molotov cocktails” had begun in Kostiantynivka. Propaganda called it the “Kostiantynivka riot” (Ukraine.ru).

“Residents at the rally demand that the Ukrainian army be withdrawn from Kostiantynivka” (Gazeta.ru).

During the day immediately after the fatal accident, the police were inactive, but at night they managed to persuade the protesters to go home.

The Kremlin's agents continued to stir up hostility in Ukrainian cities in the east, labeling and diagnosing people. Ukraina.ru called the situation in the city “the most frightening symptom of Kostiantynivka,” where “locals become terrorists and separatists simply for protesting; there are more unaccounted-for weapons than necessary; there are many drunk people with weapons; soon, ordinary Ukrainians will have nothing left to lose.”

In spring 2015, analyzing the tragedy in Kostiantynivka and the Ukrainian authorities' response to events in Donetsk Oblast in general, the Ukrainian publication Detector Media concluded that the long-standing information vacuum in the region had contributed to the spread of Russian narratives: "Six months ago, we believed that separatism in Donbas was the result of Russian propaganda during and after the Maidan — ‘fascists’, ‘junta’, ‘persecution for speaking Russian’, ‘walking around with swastikas’. And that as soon as the Donbas residents saw that this was not the case, all the tension would dissipate like smoke. This did not happen: even in the territory liberated more than six months ago, a very significant part of the population is against Ukraine. What does this mean? That Russia had been preparing for the current events for a long time, fundamentally and persistently. Post-Maidan propaganda was like pulling the trigger on a weapon that had been aimed for a long time. As a result, the anti-Ukrainian sentiment of many Donbas residents is deep-rooted, not superficial.

Documentary photographer Anatoliy Stepanov also believes that the information war began long before the events of 2014–2015, and was largely facilitated by the Ukrainian government's misguided position: "[...] What happened was planned long before April 2014. It was a special operation — clearly defined and calculated. Russia was not doing this for the first time. Everything happened according to a well-established pattern — like a carbon copy. Perhaps it was necessary to act very harshly from the very first day — to ‘take them down’,” says the photographer from the UAAP. “And Donbas is a separate story. This region had been under Russia’s informational influence for years. Russian television was operating there, people were being manipulated for years, and in the end, fertile ground was created for the Russians. In essence, this is on the conscience of the Party of Regions. They made Donbas their “fiefdom.” And as a result, everything happened there, because nowhere else in Ukraine was there anything like it — only there."

Russia had no intention of backing down from its plans. The propaganda publication Ukraina.ru predicted that there would be many more similar spontaneous events caused by the current Ukrainian government, and that the “erosion of civil war” would grow.

The Russian Federation was preparing for a full-scale invasion and was confident of a quick victory: “The civil war cannot be limited to the separate districts of Luhansk and Donetsk regions specified in the Minsk agreements,” wrote Ukraine.ru.

2022–2024. “Industrial Kostyantynivka with a Ukrainian Armed Forces garrison in the city.”

At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the Russians already tried to break through to Kostyantynivka via Lyman and Izyum, but a successful counteroffensive by the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the fall of 2022 prevented the occupation plans from being realized.

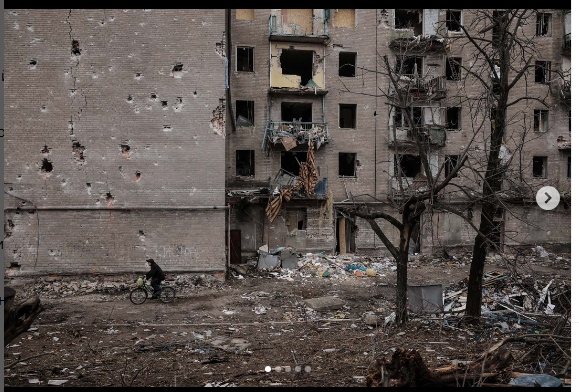

Kostiantynivka watched the war from relative safety — destroyed by Russian shelling, but free thanks to the efforts of the Ukrainian military. As the front line approached, the city changed its appearance, acquiring the scars of war.

Kostiantynivka — a frontline city, a logistics and railway hub — is a military target for terrorist strikes by the Russian army. At the very beginning of the full-scale invasion, the population of the region was evacuated by rail, and later the station ceased to operate. In February 2024, Russian missiles destroyed the railway station in Kostiantynivka.

The Russians often justify their terrorist strikes on civilian infrastructure and disproportionate attacks (with little likely military benefit compared to the large number of civilian casualties) as “legitimate” military targets.

August 9 marks one year since the Russian shelling of a supermarket in Kostyantynivka, where up to 50 civilians were present at the time of the strike. Fourteen of them were killed and 44 were wounded.

The enemy struck with an X-38 missile, burning down more than a thousand square meters of shopping aisles, destroying a Nova Poshta branch, and damaging private homes, shops, and a car wash. The Russians then called the supermarket a “military target,” shifting all responsibility onto the enemy.

Nothing changes: “product detonation” and “civilian electronic warfare.”

Today, a hypermarket in Kostiantynivka, which was used by the Armed Forces of Ukraine as an ammunition depot, was hit, writes military correspondent Kotenok. Bandera's public figures, of course, are spreading the word about the “strike on a civilian object.”

Apparently, according to Bandera's propaganda, civilian cars must drive around with Ukrainian Armed Forces crosses and electronic warfare stations on their roofs.

And only carbonated drinks and chicken fillets are burning in the supermarket."

The American media company CNN reported on this terrorist attack in an article about the Ukrainian Armed Forces' special operation in Kursk, which began a few days before the shelling of the hypermarket in Kostiantynivka.

"Moscow responds with fire. On Friday, local officials reported that at least 14 people were killed and 43 wounded in one of the deadliest attacks in recent weeks as a result of a Russian strike on a supermarket in Kostiantynivka, a town near the front line in eastern Donetsk region.

Although Moscow does not need a reason to attack civilian areas in Ukraine, such strikes usually occur after setbacks or humiliations on the battlefield," CNN writes.

2025. “The gateway to the last agglomeration in Donbas not controlled by Russia”

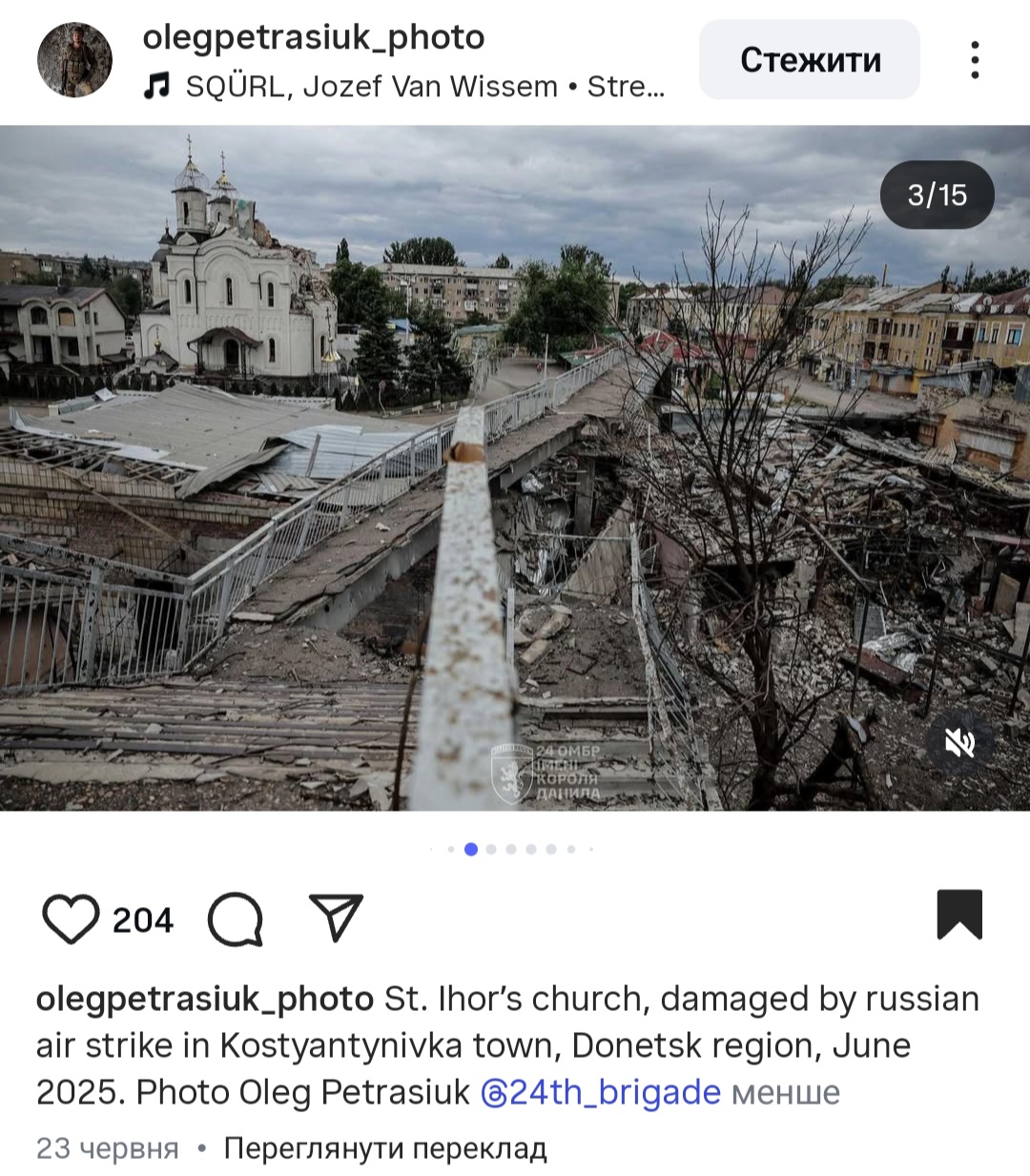

Summer 2025. The war is approaching Kostiantynivka. Toretsk and Chasiv Yar are being held at the cost of incredible efforts by Ukrainian defenders. These cities are located on high ground, so holding them is strategically important for the defense of Kostiantynivka. Pokrovsk is also holding out. According to the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, this is where most of the fighting is taking place.

Kostiantynivka, a town on the banks of the Kryvyi Torets River with a glorious industrial history during the Soviet era, has turned into a city on the brink of a humanitarian catastrophe, frozen in constant anxiety, entangled in fiber optic cables from Russian drones.

This is how photojournalist Konstantin Liberov saw the city this summer: "If you drive into Kostiantynivka today, at first glance, everything doesn't look so bad. But only at first glance. The city is completely controlled by enemy drones via fiber optic cables. The wires are everywhere. It's like a relatively intact city from which life has been sucked out, a ghost town. Only from time to time do pickup trucks fly by at top speed on broken roads, with guys sticking their heads out of the windows and trunks, pointing loaded shotguns at the sky."

Russian propaganda “war correspondents” are rubbing their hands: battles for control of the areas adjacent to Kostiantynivka are necessary to establish fire control and destroy Ukrainian logistics. In the long run, this could lead to a partial encirclement of the city on three sides.

“Kostiantynivka, which had a population of about 67,350 before the conflict began, forms the basis of this offensive and serves as a gateway to the last major agglomeration in the region not controlled by Russia — Sloviansk, Kramatorsk, and Druzhkivka” (Lenta.ru).

The capture of Kostyantynivka may become the main goal of the Kremlin's summer military campaign.

“The capture of Kostyantynivka will destroy the entire Ukrainian defense in Donbas,” says Zymovsky (media consultant, military expert — author).

In general, Kremlin propaganda outlets have varying expectations for the summer campaign in Donetsk Oblast: from pessimistic to almost festive.

“We have every reason to believe that during the summer campaign, the goals of the SVO — the demilitarization of Ukraine and the liberation of territories — may be partially achieved,” the expert said (Ukraine.ru).

The Kremlin's thesis about the “liberation of the entire Donbas” is key to justifying Russia's unprovoked invasion. On June 30, the head of the occupation authorities, Leonid Pasichnyk, assured that the territory of the so-called “Luhansk People's Republic” had been completely liberated.

As Detector Media reported, Pasichnyk's words were not backed up by comments from the Russian Ministry of Defense, and his announcement of the “complete liberation” of Luhansk was ridiculed by Russian military propagandists, who pointed out the fake “victory.”

Propaganda is trying in every way to refute the obvious fact that Russia is unwilling to end the war despite the negotiations that have begun. They say that “they have demonstrated sufficient readiness for the peace process” and are now “trying to worsen Kyiv's position in future negotiations by depriving it of the opportunity to defend itself on convenient lines and hold logistical routes” (Yulia Vityazeva's Telegram channel).

“Fake: The battles for Chasiv Yar demonstrate that Russia has no intention of ending the conflict, and the city itself has completely lost its strategic significance, according to Forbes.”

In fact, in its article dated July 4, 2024, Forbes quotes retired Australian Army General Mick Ryan, who assessed Russia's successes on this section of the front. He says that the Russians have made some progress in their offensive on Chasiv Yar, but their losses amount to 99,000 soldiers. A year has passed since then.

That is why it is important for propagandists to somehow justify these insane losses: the “Kyiv regime” turned Chasiv Yar into a fortified stronghold on a hill in the middle of the steppe in an area with branching rivers. This, they say, allowed the Armed Forces of Ukraine to use Chasiv Yar to defend Kostyantynivka, an important logistics hub through which roads lead to Pokrovsk, Kramatorsk, and Sloviansk. But they assure us: “The epic battle for Chasiv Yar, which covered the industrial town of Kostyantynivka, with the Armed Forces of Ukraine garrison is coming to an end” (Telegram channel “War Against Fakes”).

Near Toretsk, 20 km south of Kostyantynivka, the Russians also suffered catastrophic losses — 70,000, including 20,000 killed, as Sergei Khominsky, press officer of the 100th Separate Mechanized Brigade, said on Hromadske Radio.

Russia spent the winter of 2024–2025 improving the coordination of missile and drone strikes and mobilizing troops for infantry assaults. In addition, the Russian Federation transferred elite troops to the Chasiv Yar and Pokrovsk directions. Due to the lack of success in the Chasiv Yar direction, the Russian Federation was forced to involve a separate presidential regiment of the FSB in the assaults, according to Suspilne Donbas, citing a spokesperson for the 24th Separate Mechanized Brigade named after King Danylo.

The propaganda publication Tsargrad predicts the fall of another fortress city west of Kostiantynivka — Pokrovsk. Propagandists are interested in which directions Ukrainian defenders will leave: "The success of this operation could lead to the fall of the city without a frontal assault. The Armed Forces of Ukraine will, so to speak, face a dilemma of whether to leave the city or cover the Pokrovsk direction, because it is not far from Pavlohrad, an important center of Ukraine's defense industry" (Tsargrad).

In the Kostyantynivka-Pokrovsk direction, the Ukrainian military is opposed by a new Russian unit, Rubicon, which was transferred from the Kursk direction. Well-equipped and directly subordinate to the Russian Ministry of Defense, Rubicon uses experimental types of drones, which has significantly complicated the work of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Konstantin Liberov spent time with the fiber optic unit of the 28th Brigade in Kostyantynivka to figure out how FPV drones work on fiber optics. He says that there are not many brigades and units in the Armed Forces of Ukraine that use this technology in combat due to the high cost and scarcity of fiber optics and the time required for training. The technology is very simple and at the same time deadly.

"A fiber optic drone cannot be neutralized with electronic warfare. The only option is to shoot it down in the air when it already sees you and is flying towards you. That means you only have a few seconds. And very often this fight is futile."

Texty.org reports that the summer offensive is being presented to Russian soldiers as a “final push” aimed at breaking the morale of Ukrainians. Together with constant terrorist shelling of Ukraine, the Kremlin is trying to impose the idea of the inevitable defeat of Ukrainians in the war.

In such difficult conditions, the most effective thing seems to be to help the Ukrainian army and to recognize Russian propaganda in the flow of media reports about the Russian-Ukrainian war in a timely manner. The Ukrainian Association of Professional Photographers will continue to assist its readers in this regard by debunking hostile fakes, IPSO, and exposing propaganda narratives.

Contributors:

Researcher, author: Yana Yevmenova

Image editor: Olga Kovaleva

Literary editor: Yulia Futey

Website manager: Vladislav Kukhar

%20(750%20x%20360%20%D0%BF%D1%96%D0%BA%D1%81.).png)